- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

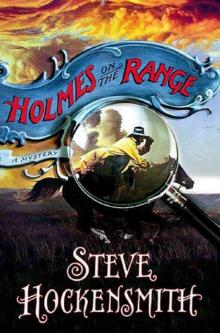

Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Read online

HOLMES ON THE RANGE

HOLMES

on the

Range

STEVE HOCKENSMITH

ST. MARTIN’S MINOTAUR

NEW YORK

HOLMES ON THE RANGE. Copyright © 2006 by Steve Hockensmith. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.minotaurbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hockensmith, Steve.

Holmes on the range / Steve Hockensmih.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-34780-4

EAN 978-0-312-34780-2

1. Cowboys—Fiction. 2. Brothers—Fiction. 3. Ranch life—Fiction.4. Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sir, 1859–1930—Appreciation—Fiction. 5. Montana—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3608.O29H65 2006

813’.6—dc22

2005050406

First Edition: February 2006

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR MAR, OF COURSE

HOLMES ON THE RANGE

PROLOGUE

Or, The Calm Between the Storms

There are two things you can’t escape out here in the West: dust and death. They sort of swirl together in the wind, and a fellow never knows when a fresh gust is going to blow one or the other right in his face. So while I’m yet a young man, I’ve already laid eyes on every manner of demise you could put a name to. I’ve seen folks drowned, shot, stabbed, starved, frozen, poisoned, hung, crushed, gored by steers, dragged by horses, bitten by snakes, and carried off by an assortment of illnesses with which I could fill the rest of this book and another besides.

So it’s quite a compliment I bestow when I say that the remains we came across the day after the big storm were the most frightful I’d ever seen. Not only had a few hundred cows gone for a waltz over the body, prairie wolves had snacked on whatever hadn’t stuck to the hooves. The remaining dribs and drabs of gristle were mixed in with the mud like strips of undercooked beef in a bowl of Texas chili.

“I’ll get to gatherin’ up the bits,” my brother said as he swung down off his saddle. “You head back and grab us a couple shovels.”

Usually when Old Red gets bossy with me—which is only about a hundred times a day—I repay his piss with vinegar. But my brother got no sass from me now, as fetching tools sounded a hell of a lot more appetizing than separating innards from earth.

It was a morning as lovely as a Montana spring can produce, so cool and calm and sunny-bright you’d hardly think the blue sky above was the same one that had roiled with black clouds and lightning just hours before. I enjoyed a leisurely ride to headquarters and back, making the most of a rare moment of solitude in the sunshine. Old Red and I had been working the Bar VR ranch nearly two months now, and this was my first opportunity to be alone that didn’t involve an outhouse and the attendant odors thereof. True, a man I knew had just died in as messy a manner as one can imagine, but you can’t fault me for appreciating a beautiful day while I could. I’d get my fill of ugliness soon enough.

I found Old Red knee-deep in ugly when I returned. Whereas before the “body” had been little more than a colorful circle in the mud, my brother was now shaping the raggedy chunks of flesh and bone into the approximate shape of a man.

“He ain’t Humpty Dumpty,” I said, tossing a shovel at Old Red’s boots. “You can’t put him back together again.”

My brother made no move to pick up the shovel. Instead, he wiped his hands on his Levi’s, pulled off his Stetson, and ran his fingers through his close-cropped, cherry-red hair. He usually wears upon his face an expression of vaguely irritated disappointment, as if he can’t stop stewing on what he would’ve done with those six days God took to make a botch of the world. But he didn’t look vexed or even disgusted now. He merely looked puzzled.

“It ain’t him I’m tryin’ to piece together,” he said, rubbing the back of his head like it was a magic lamp and he was Aladdin trying to coax out the genie.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I asked as I unhorsed myself.

“I’m tryin’ to put together how he got like this.”

“Well, I reckon some cows might’ve had somethin’ to do with it,” I said, quickly plunging my shovel into the soppy muck. If I had to bury a body that looked like an explosion in a butcher’s shop, I wanted to get it over with fast. “That’s the only way I can figure it . . . unless you spotted some elephants out this way yesterday.”

One day maybe I’ll get a laugh out of my elder brother. This was not that day.

“I’m just wonderin’ if those cows had ‘em some help,” he said.

I froze mid-dig. Without quite knowing it, I’d been waiting for this moment for months. It was like waking up at the sound of a train whistle—and remembering you’d fallen asleep on the tracks.

“Damn it, Brother,” I said. “You’re a cowboy, not a detective.”

Old Red didn’t answer with words. He just turned and showed me that little wisp of a grin he slips under his mustache when he thinks he’s being clever.

Oh? his smile said. A feller can’t be both?

One

THE BEGINNING

Or, My Brother “Deduces” His True Calling

You can follow a trail without even knowing you’re on it. You start out just ambling, maybe get to thinking you’re lost—but you’re headed somewhere all the same. You just don’t know it till you get there.

That’s how it was with me and Old Red. We’d got ourselves pointed at that flapjack-flat body a full year earlier, in the spring of 1892. All it took to get us moving toward it was a magazine story.

We were working a cattle drive at the time, and one night by the campfire one of the other drovers pulled out a detective yarn called “The Red-Headed League.” It was meant as a jape, as my brother and I form a sort of “red-headed league” ourselves. We’ve got hair red enough to light a fire, and though our tombstones will read “Otto Amling-meyer” and “Gustav Amlingmeyer,” up and down the cow trails we’re known as Big Red and Old Red. (I was branded Big Red for the obvious reason—size-wise I’m just a shade smaller than your average house—while Gustav won his handle more for attitude than decrepitude, having as he does a crotchety side more befitting a man of seventy-two than twenty-seven.)

Old Red not being on speaking terms with the alphabet, it was up to me to read “The Red-Headed League” out loud. And I enjoyed doing so, for I found it to be a dandy little tale. But my brother took it to be a lot more than that. To him it was a new gospel.

Some folks get religion. Gustav got Sherlock Holmes.

As you most likely know, this Holmes fellow’s an English detective who’s world famous for his great “deductions.” Only we’d never heard of him, being out here in Montana where we’ll probably only find out about the Second Coming by telegraph a week after it happens.

In “The Red-Headed League,” Holmes busts up a gang of desperadoes just about single-handed. But it wasn’t the what of the story that got under my brother’s skin so much as the how. Holmes had him this way of digging out facts just by noticing what most people ignore. He could tell where you were born by shaking your hand and what you had for breakfast by how you combed your hair.

“He didn’t catch them bank-robbin’ snakes with some trick he learned at a university,” Old Red said to me. “He caught ‘em cuz he knows how to look at things—look and really see ‘em.”

I guess that would appeal to a fellow like my brother, who had his one year of school

ing so long ago it’s a wonder he can remember one plus one equals two. He asked me to read that story to him over and over in the months that followed, and not once did I refuse, for read-ing’s a skill I wouldn’t even have were it not for him. (When I was a child, Gustav and my other brothers and sisters worked extra hours at their chores so at least one of us—me—could get some decent book-learning. I was supposed to hoist the family up into the merchant class, only smallpox and floodwater swept most of us up to heaven before I could do much in the way of hoisting myself.)

The more Old Red heard “The Red-Headed League,” the more he got the idea that he had the makings of a fine detective. As I’m his younger brother, you might think I’d be inclined to poke a pin into such puffed-up notions. But I’d always figured Gustav was meant for more than roping steers. While he’s every bit as undereducated as your average puncher, he’s by no stretch underthoughtful. He’s prone to long stretches of cogitation and contemplation on matters he barely even knows the words to put a name to, and I’ve often thought if he’d been born the son of a senator instead of the son of a sodbuster, he would’ve become a philosopher or a railroad tycoon instead of a dollar-a-day cowhand.

So I tolerated Old Red’s fixation on detectiving, even if I couldn’t see any practical use for it. As it turned out, there was something else I couldn’t see: how much trouble it could get us into.

Not that we were in great shape when that trouble began. The bank in which we’d been saving our trail money had gone belly-up, and we’d drifted to Miles City with nothing left of our nest egg but a few dollars in our pockets and fond memories in our hearts. It was February, so the spring roundups—and the jobs that come with them—were months off. If we were going to get through the winter without selling our saddles and eating our boots, we needed a miracle and we needed one quick.

Now, waiting for a miracle can be a disheartening business. I purchased what solace I could with the two bits Old Red gave me to parcel out each day in the town’s saloons. My brother tagged along, though not out of desire for drink or companionship. He wanted to make sure I didn’t start a tab anywhere. And he had another reason, too: He was practicing his Holmesifying.

While I shared watery beer and dirty jokes with whatever partners I could rustle up, Old Red sat quietly, casting a cold eye on anyone who came through the door. He was testing himself, trying to make Holmes-style deductions—I wasn’t allowed to call them “guesses”—based on a person’s appearance. He wasn’t bad at it either, though I wouldn’t let him forget the time he told me a fellow was a bounty hunter with a wooden leg. Turned out he was a blacksmith who’d dropped an anvil on his foot.

Old Red did most of his Sherlocking in a dingy little hangout called the Hornet’s Nest, which caters to drovers whose luck has taken a turn for the unfortunate. Naturally, that’s where we were the day our luck went from bad to worse. It was well before noon, and I was still nursing my first beer of the day when Gustav sent an elbow into my ribs and whispered, “Take a look at these fellers.”

I glanced up and saw two big men moving toward the bar. They had no need to shove—they were rough-looking hard cases indeed, and the crowd before them simply parted like the sea before Moses. When they reached the bar, they barked out for whiskey.

“Those two move with confidence,” Old Red said, talking low. “And I’d say they’ve earned it somehow, cuz they’re puttin’ a real scare on the boys. They ain’t got fancy enough artillery to be gunmen, though. And just look at the wear on those clothes. They’re punchers—but not just any punchers. Men in command. A ranch foreman and his straw boss, I’d say.”

I shrugged. “Could be.”

“No ‘could be’ about it.” My brother lifted a finger just high enough to point out the larger of the two men, a black-bearded, meat-heavy gent even taller than me. “I’d bet our last buck that’s Uly McPherson.”

I knew of the man. He was the foreman of a nearby ranch: the Bar VR. He had himself quite a reputation—not that I’d heard much specific. I’d simply noticed that anytime his name came up, folks were too busy looking over their shoulders and wetting their drawers to keep talking.

“That’d explain why the boys ain’t crowdin’ him,” I said. “Once he’s gone, we’ll ask the fellers if you deducted right.”

The two men picked up their whiskeys and washed their tonsils. Then the bigger one slapped a coin on the bar, and they started to mosey out. But when they reached the doorway, they didn’t push through. Instead, they turned to face the room.

“Listen up,” the big one said, not shouting, but with a strong, clear voice that grabbed your ears hard even without a whopping lungful of air behind it. “I’m lookin’ to hire hands to work the Bar VR at five dollars a week.”

Old Red had been right: It was Uly McPherson.

He looked more like a small-time nester than the top screw of a big ranch. His battered Stetson had lost so much of its shape it drooped over his head like a saddle, and his clothes were held together with the sloppy patchwork you see on bachelor farmers. His large, round face obviously hadn’t felt the touch of a razor in months.

I pegged the fellow with him as his brother, Ambrose. He looked to be a tad older than me, which would put him just north of twenty. Folks around town called him Spider, though I didn’t know why. With his puffed-out chest and dark, unblinking eyes, he reminded me more of a rooster. His lean face was smooth-shaven, but otherwise he was as shabby as his brother.

They looked like men who didn’t give a shit what other men thought of them, and I felt pity for any drover dumb enough to sign on with their godforsaken outfit.

“I need waddies who can ride, rope, stretch wire, grease a windmill, and take orders without backtalk,” McPherson said. “If you think that’s you, line up.”

There was a long, quiet moment while everyone mulled that over. Then a gangly fellow called Tall John Harrington pushed off from his perch and moved to the middle of the room. After that, more men found the courage—or desperation—to do likewise. I turned to Gustav, about to thank God we hadn’t sunk so low, only to discover that we had.

Old Red was standing up.

“No,” I said.

“Yes,” he said.

And that was the end of the debate. Gustav wasn’t just my elder brother—he was the only family I had left. I’d been stuck to his bootheel for four years, and while he’d walked us into a few tight spots, he’d always walked us out again.

So I got to my feet, and the two of us joined the cowboys trying to form a line. A few were dizzy with drink despite the early hour, making it bumpy work, but we finally got ourselves into a ragged, slouchy row.

We were a scruffy-looking bunch, but you could form a fine outfit if you put us to the test and chose carefully. Some ranches have tryouts that last days, with dozens of drovers busting broncs and throwing calves until all the spots in the bunkhouse are filled. I figured that’s what McPherson had in mind. He’d ask a few questions, see if he recognized any names, then take us to a corral to make out whose riding was as good as his talk.

McPherson sized us up, then walked over to the man at the far-right end of the line. Here we go, I thought, as the fellow he was moving toward was Jim Weller, a Negro puncher with a reputation as a top-drawer hand.

McPherson stepped right past him.

“One,” he said, pointing at the man to Weller’s left. He moved to the next man. “Two.”

From there he went to three and four and so on in the order you might guess. Gustav was five. I was six. Tall John Harrington was seven—and the last one picked.

“Alright, boys,” McPherson said. “You’re hired.”

Two

OLD RED’S RAVE-UP

Or, My Brother Discovers a Cure for Lockjaw

McPherson told us when to show up at the ranch and the trails to take to get there, and then off he and his brother went, leaving behind a shocked silence that hung so heavy on the room it could’ve smothered a cat.

&nbs

p; This was simply not the way a big outfit picked hands. And why hire up now, with snow still on the ground and the spring roundups weeks off? It just didn’t figure.

The cowboy to Tall John’s left broke the quiet by swiping his hat off his head and throwing it at the floor. “God damn! I’m eight out of seven! Am I the unluckiest son of a bitch ever or am I not?”

Most of the boys busted out with guffaws, but Jim Weller didn’t even unpack a smile.

“If anyone’s had the silver linin’ swiped off his cloud, that’d be me,” he said.

No one had a reply to that, for though the Negro drover was well thought of by those willing to think, not everyone falls into that category—as McPherson seemed to prove. Conversation that separated the open-minded from the muleheaded was best avoided lest you were fishing for a fight.

It was Old Red, of all people, who put some cheer back in the room. Most days he takes to fun like a duck to fire, or you might say like oil to water. But this day was different.

“Here’s a silver linin’ for you, Jim,” he said, and he pulled out a ten-dollar note and handed it to me. “You know what to do with this, Brother.”

I stared at him as if he’d just pulled the king of Siam from his pocket.

“You sure?”

“I’m sure.”

I let out a whoop and called for the bartender to pour a beer down every throat in sight. Old Red and I were mighty popular while that ten dollars lasted. Once it ran out, other fellows took to buying rounds, either to toast their good luck or drown their bad.

Somewhere in there a twister hit town, or at least it hit me, for when I awoke the next morning our little hotel room was spinning like a top. Yet when Gustav pulled the sheets off me and barked, “Let’s go,” I managed to roll my aching carcass out of bed, haul it downstairs, and drag it atop a horse—but just barely.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

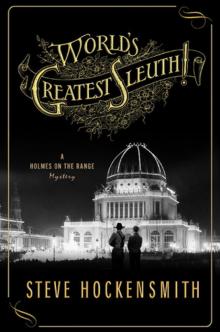

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!