- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Page 10

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Read online

Page 10

"I see," Bucket said with gentle sympathy. "Well. I'm sure I've taken up enough of your time this evening. I'll bid you a merry Christmas and be on my way."

"If by some miracle this is a merry Christmas, it will be my last," Cratchit moaned, wringing his hands. "I can't imagine much merriness in debtor's prison."

"Now, now, Mr. Cratchit—" Bucket began, sidling toward the door.

"The carolers may be singing of glad tidings for man, but the tidings for this man couldn't be more woeful," Cratchit continued, staring up at Bucket with wide, round, red eyes. "I hear no Christmas carols, sir. I hear dirges."

"Now, n- —," Bucket tried again.

"Alas," Cratchit broke in, "it is a blessing after all that there will be no loving family gathered 'round me come Christmas morning. For how could I keep them from starving when I can't even keep my own stomach full? Why, I haven't even the money to buy a single hot cross bun!"

And at last Bucket understood: He could not exit Cratchit's chambers without first paying the toll.

"You've been very helpful, Mr. Cratchit." Bucket scooped a few pennies, farthings and half-farthings from his vest pocket and handed them to the clerk. "Please, allow me. In the spirit of the holiday."

"Thank you, Inspector." Cratchit eyed the small bulge that remained in Bucket's pocket, his hand still outstretched. "This should stave off starvation till Boxing Day, at least. As for my little ones . . . well, I still can't so much as send them a lump of coal, but perhaps the warmth of their poor mother's love will be enough to keep them from freezing."

Bucket sighed, dug in his finger again and produced a sixpence. It landed atop the other coins in Cratchit's palm with a hard, cold clink.

"Bless you," Cratchit said, pocketing the coins with a nod that let Bucket know he'd finally been dismissed.

The detective scurried out the door before Cratchit could change his mind and begin wheedling again. The man was so good at it, Bucket was afraid he'd leave the flat with nothing but the clothes on his back, if that.

"Where to now, Inspector?" Dimm grumbled as Bucket climbed back atop the ambulance with him.

A light snow had been falling, yet the constable was too lethargic to brush any of the accumulation from his coat, and he was dusted in white from top to bottom. It looked as if pranksters had left the wagon-reins in the hands of a snowman.

"One last stop, then you're through playing hansom driver, Police Constable Dimm."

"And where might we be going now? Z Division? Or do you need to interview someone in Aberdeen, perhaps?"

"Not nearly so far," Bucket replied cheerfully. Though he'd be leaving Camden Town more than half a shilling lighter than he'd entered it, he was in far too good a mood to let Dimm's insolence provoke him. "Bloomsbury will do. 126 Southhampton Row. The Bucket residence."

It was a long, cold ride south to Bloomsbury, but Bucket barely felt the chill. He was warmed by thoughts of the pipe, slippers, sherry, poultry and pudding that awaited him—not to mention the genial Mrs. Bucket. He was warmed, too, by the glow of self satisfaction.

The Mystery of Ebenezer Scrooge had proved to be no mystery at all.

After sending Dimm on his way with spirited holiday well wishes (which the constable acknowledged with but a grunt), Bucket stepped inside his cramped-yet-comfortable home to find his usually imperturbable wife flushed and panting.

"Oh, William!" Mrs. Bucket exclaimed, throwing her plump arms around him. "When I saw that ambulance out front, I didn't know what to think!"

"There, there, my pet," Bucket said, comforting her with a squeeze and a peck on the cheek. "I'm sorry for the fright. I should've had Police Constable Dimm drop me at the corner. As you can see, there's nothing wrong with me a hot supper and a cuddle by the fire won't cure."

Though the Buckets occasionally took in lodgers, they had none now, so the mister felt free to give the missus a playful swat on the behind as he disentangled himself from her arms and headed for the kitchen.

"If you think you're getting out of trouble that easily after coming home three hours late on Christmas Eve . . .," Mrs. Bucket mock-scolded, her fists perched on her wide hips.

"Late?" Bucket dipped his forefinger into a pot of thick, brown gravy. "Oh, no! I'm early! Just look on the mantelpiece if you don't believe me."

While the inspector loaded a plate with the roast duck, stuffing and pudding he found warming in the oven, his wife went to the drawing room and searched the mantel. Tucked away behind a portrait of Sir Robert Peel she found a small black book bound with red ribbon: Tales, by Edgar Allan Poe. Eyes gleaming, Mrs. Bucket ripped the ribbon free and practically hurled herself into the nearest chair. By the time her husband joined her in the drawing room, his round belly all the rounder for the two heaping plates of food he'd just consumed, she'd already raced through "The Gold-Bug" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" and was plunging headlong into "The Murders in the Rue Morgue." Bucket knew it was useless to attempt to engage her in conversation until she'd finished, so he settled back into a chair of his own, propped his feet up before the fireplace, lit his pipe and waited.

A few minutes later, his wife heaved a contented sigh, closed her book, and looked up at Bucket with a smile.

"Thank you, William," she said. "So . . . now you can tell me your mystery story."

Bucket grinned back at her. There'd been no need to tell her what had kept him late. It had to be a case, and a particularly interesting one to boot. And, as with all such cases, Mrs. Bucket would want a full accounting from her husband—as well as the opportunity to test her own observations and inferences against his. And Bucket was happy to oblige her, for he'd found that his wife's conjectures stocked a far greater store of logic and insight than those of his colleagues.

So he told her the tale. Mrs. Bucket sat rapt throughout, not speaking a word for nearly a quarter of an hour. She merely cocked an eyebrow or murmured the occasional "hmmm" until Bucket clapped his hands together and said, "And then I came home to find my dear wife on the verge of fainting! So? What do you make of it all?"

Something about the quizzical look in his wife's eyes tickled Bucket's forefinger like a feather.

"Why do I get the feeling, William, that you are on the verge of making an arrest?"

"Because you're a deucedly clever woman—and because I am on the verge of making an arrest!"

"But who will you arrest?"

"Why, the nephew, of course!"

"Mr. Merriweather?" Mrs. Bucket shook her head. "He sounds like such a nice, jovial man."

"So he seems," Bucket said, the tickle in his finger deepening into a disconcerting prickling. "But consider this, my plum: Mr. Fred Merriweather is the only person in the world who stands to gain by the death of Mr. Ebenezer Scrooge. The old man was hostile to the very notion of altruism . . . except when under the influence of opium. So it's unlikely that Mr. Scrooge would bequeath his holdings to the church or some charitable society. And those who had cause to hate Mr. Scrooge the most—the many men in his debt—had the most to lose from his death, since their chits might simply be handed over to an even more rapacious creditor."

Bucket paused to gauge how his reasoning was being received. His forefinger didn't like what his eyes reported: Mrs. Bucket's mouth had developed an infinitesimal tilt, one corner of her full lips curling ever-so-slightly upward.

It didn't bode well. Yet Bucket forged on.

"Second, consider the death of Mr. Merriweather's child. Not only would this deepen Mr. Merriweather's antipathy for his uncle—Mr. Scrooge didn't attend the funeral, you'll recall—but it could have created another motive for murder, as well. Even after the spirit departs, the bills remain. A long illness, a burial, a year in mourning dress. It all costs money. In fact, death is such an expensive proposition these days, I daresay most of us can't afford it! Yet when it comes time to pay the ferryman, we can't refuse, and those we leave behind must settle the tab. It's made paupers of more than one prosperous family. Perhaps Mr. Merriwea

ther found it necessary to, shall we say, accelerate the scheduling of his inheritance."

Bucket's forefinger was itching and sweating now, for Mrs. Bucket's smile had grown wider. But the finger had one more card up its sleeve, so to speak.

"Third, consider the smell of opium smoke I detected upon Mr. Scrooge—and remember that Mr. Merriweather specializes in 'imports from the East.' Surely, a businessman with dealings in the Orient might easily develop connections with the China opium trade or the poppy fields of Afghanistan. And for what purpose did Mr. Merriweather visit his uncle's offices today? To offer 'Christian forgiveness' by inviting Mr. Scrooge to a holiday party hosted by a grief-stricken woman who openly loathes him? That's offering an olive branch with a wasp nest attached, wouldn't you say? Yet it gave Mr. Merriweather an excuse to be alone with his uncle for a few minutes . . . and that was all the time he needed to set his fiendish plot into motion."

Bucket leaned back in his chair and put his pipe to his lips for a triumphant puff—and only noticed then that there was no puff to be had, the tobacco's low flicker of fire having long since snuffed out.

Mrs. Bucket's smile, on the other hand, had been kindled into full flame.

"I'm curious, William," Mrs. Bucket said. "By what means did Mr. Merriweather 'set his fiendish plot into motion'?"

Bucket's forefinger rubbed the cold curve of his pipe-bowl, as if it might relight the tobacco within through sheer friction. Blast her (and bless her) his wife had found the hole in his case, as she always did when there was a hole to be found.

"You mean how did he administer the opium to his uncle? That I shall discover when I return to Mr. Merriweather's home after Christmas. With a search warrant."

"I see," Mrs. Bucket said in a way that suggested she saw much more than her husband.

"You have another question for me, Mrs. Bucket?"

"I do," Mrs. Bucket said. "I wonder why you assign such importance to Merriweather's access to opium via trade connections when it's so readily available through alternate means. Might a doctor not have a sample amongst his supplies? Wouldn't someone who had access to, let's say, the medical kit in a police ambulance be able to make off with some variant, such as morphine? And, my goodness—you won't find a more popular bottled remedy than laudanum, and it's little more than opium sweetened with sugar."

For the full length of a minute, Bucket made no reply. His wife hadn't just pointed out a hole. She'd pointed out that his theory about Merriweather was nothing but hole.

"What you say is true," he finally admitted. "But even if this hypothetical doctor or ambulance driver or laudanum user had equal access to opium, you must admit that none would have as potent a motivation for using it."

"Well," Mrs. Bucket said, shrugging in a way that indicated she would admit no such thing, "I find it rather hard to understand why anyone would want to use it on Scrooge."

"What? Ebenezer Scrooge was one of the most hated men in London!"

Mrs. Bucket nodded calmly. "Yes, he was. So if he had been murdered, I should think you would have a city full of suspects to sort through. But, William—Scrooge wasn't murdered, was he? He ran into the street and was trampled by a passing wagon. His death was an accident."

"How can you say that? The opium—!"

"Would have made a poor murder weapon. If Scrooge's death had been the objective, surely arsenic would have made a better choice. Or any of a hundred other poisons."

"But . . .!" Bucket began, his forefinger poised to give his arguments renewed life through vigorous pointing and waggling. The finger quickly went limp, however, and the rest of the detective followed suit, settling back into his chair with a defeated sigh.

"You're right," he said. "I'm a fool."

Mrs. Bucket reached over and gave her brooding husband a brisk (but not too forceful) swat on the arm.

"What a thing for Inspector William Bucket to say! The man who unmasked the killer of Theopholus Tulkinghorn and rescued Edwin Drood from the clutches of the devious Canon Crisparkle? The man who engineered the capture of Reginald Compeyson and Tom Gradgrind? The man who pulled the secret strings that sent the fiends Orlick and Fagin to the gallows? The man who married me? A fool? I think not! You've simply been asking yourself the wrong questions tonight. Set your mind to the right ones, and we'll soon see who's a fool!"

"Well . . . perhaps." Bucket pushed himself deeper into the cushions enveloping his broad undercarriage and tried to revive his fatigued and dejected forefinger by rubbing it across his chin(s). "So 'the right questions' would be . . . ."

"Who would have preferred to see old Scrooge drugged rather than dead, and why?" his wife finished for him.

"Ahhhh . . . ."

The detective bolted to his feet with his arm upraised and his forefinger pointed skyward, as if he were a puppet hoisted aloft by a string tied to his finger.

"A-ha!"

"A-ha?" Mrs. Bucket asked innocently.

The inspector dashed to the coat rack in the foyer and began pulling on his overcoat and boots. "I've no time to explain—and no need, I'll warrant! By Jove, if Scotland Yard knew about you, half the force would be in blue skirts and bonnets inside a week. You ladies might not be as swift with a truncheon as us brutes, but you can be just as swift with a deduction, if given half a chance." Bucket affixed his hat upon his head and threw open the door. "But enough of my babblings! If there ever was any time to lose, I've misplaced it already!"

"Be careful, William!" Mrs. Bucket called as her husband rushed outside in such a hurry he didn't even close the door behind him.

"If duty permits, my pet!" he shouted without looking back. "If duty permits!"

Bucket spent the next seven minutes hustling up and down the streets of Bloomsbury looking for a hansom, all the while mumbling self-recriminations so acidic they could have melted the snow beneath his flying feet. Even after he finally found a free cab, Bucket's anxious, murmured curses continued throughout his ride, only coming to an end when he hopped out, collared a shivering street waif and sent the lad running to the Bow Street station house with a shiny new three-penny in his pocket. (Scrooge's clerk Cratchit had confiscated all the detective's smaller coins.)

The urchin had already dashed off, disappearing into the fog and snow swirling around the gaslights, when Bucket realized exactly how much rested on his messenger's honesty and speed. Looking across the street at his destination—the offices of Scrooge & Marley—Bucket beheld a dim light flickering behind the thin curtains in the window.

The inspector had arrived just in time to confront the culprit. But he would have to do so alone.

The hustle and bustle of the neighborhood had long given way to the eerie stillness of a late winter's night. Nevertheless, Bucket paused to look both ways before hurrying across the street. He was, after all, at the very spot where Scrooge had been crushed like a pea in a nutcracker hours before.

When he reached the office door, Bucket opened it slowly, dreading the shrieking squeak of rusty hinges that would alert his quarry. But the squeak never came, and Bucket crept inside. He took ginger, hesitant steps, mindful of the floorboards and the not-insubstantial strain his bulk placed upon them. He turned, closed the door, then pushed on into the darkness.

A low, fluttering glow spilled out from a room at the back of the office. As Bucket inched toward the source of the light—candles atop Scrooge's own desk, he was certain—he passed Cratchit's cramped work nook. Resting on the clerk's precarious perch of a desk were an unused candle and a box of lucifer matches. The detective picked them up and brought them to the ready as he crept forward.

He paused just outside Scrooge's sanctum, listening to a low, scratchy noise from around the corner: a pen moving across paper. Then he struck the match, lit the candle and stepped into the room.

"Working late, are we?"

The detective's theatrical entrance had the desired effect. The man seated at Scrooge's desk jumped to his feet popeyed with fright.

"Oh . . . it's

you, Inspector," Bob Cratchit said. He eased himself back down into Scrooge's seat with a smile that looked as out of place on his sallow face as jingle bells on a crocodile. "You gave me quite a scare! Yes . . . yes, I am working late. There were a few things that needed to be put in order before Scrooge's accounts are handed over to whoever—"

"What sort of things?" Bucket cut in. He nodded at the ledger spread out before Cratchit. It was the same wax-splattered account book the detective had seen there when he'd made his search of the office hours before. "From the lock on that ledger book, I'd guess Mr. Scrooge intended that only he should make changes to the balances inside."

"Well, yes . . . you're right." Cratchit's grin began to flicker like the candlelight that barely illuminated the room. "But Scrooge fell behind on the bookkeeping. There were changes he never got around to writing down."

"Payments, I assume?"

Cratchit's smile finally snuffed out completely.

"Yes . . . payments," the clerk said, his gaze dropping to the fresh ink that still glistened on the ledger book's pages. When he looked back up again, his eyes were wild with fear and remorse. "You must believe me, Inspector, I—!"

Bucket silenced him with a clucked tut-tut and a waggle of his upraised forefinger. "You don't have to explain. I know you didn't mean to harm Mr. Scrooge—at least not in the physical sense. You merely hoped to inflict a few small wounds upon his pocketbook through some surreptitious . . . editing, shall we say? Your duties have included copying Mr. Scrooge's letters, so you've had ample opportunity to master the forging of his handwriting. But getting access to his ledgers proved a thornier problem. Mr. Scrooge kept them under lock and key. So you planned to make the changes while he was in an opium-induced stupor. You could tell him afterwards that he suffered from some kind of episode—an excuse you could also use if he ever questioned your changes. 'Don't you remember, sir? Mr. Smith paid us in full the day you had your spell. Mr. Jones, as well.' And so on. I assume you were to be rewarded for your trouble. A percentage of the debts you erased, perhaps?"

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

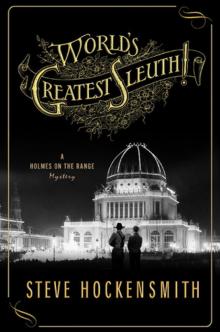

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!