- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) Page 15

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) Read online

Page 15

“Wait. Stop. Isn’t Kenneth Meldon in a nursing home?”

“Right, okay, you got me. I shouldn’t have brought him up. But the other two are worth looking at.”

“Alanis, I gave you those names because those people had complained to the police—to me—about your mother. Do you really think someone would do that and then decide to murder her?”

“Sure…if the police didn’t do anything about her.”

Logan made another pained face and turned away from me. “When is that damn steak coming?”

“One more thing.”

“We should’ve gone to Smitty’s…”

“Who would you take semi-hot jewelry to around here?”

“Oh god. Are you planning a heist now? What have I gotten myself into?”

“I said semi-hot, Logan. I’m not talking about stuff that’s been outright stolen. Just stuff you don’t want to answer any questions about. Stuff you wouldn’t want to waste on a below-the-radar fence.”

“Just tell me you aren’t trying to sell this stuff.”

“No. But I think my mom did.”

“And you’re going to get it back?”

“Possibly.”

I also wanted to find out who else had been looking for it and what their disposition had been.

This I did not say.

“All right, fine,” Logan groaned. “In Berdache, you’d go to the Fourth Street Pawn Shop. If you went a little farther afield—”

“The smart move.”

“—you might go to the Westside Gold and Jewelry Exchange in Sedona or Jones Pawn & Loan up in Flagstaff.”

“I assume you’ve already checked with all of them about the electronics that were stolen from the White Magic Five & Dime.”

“Thank you for assuming I’m not a total idiot.”

“Was a camcorder on the list of things you were looking for?”

“Yes.”

“How about a bunch of missing tapes?”

Logan frowned. “No. Clarice didn’t say anything about that. Should she have?”

“Well, it’s not the kind of thing anyone would pawn. But yeah, she should have mentioned it. I think my mother was secretly recording some of her readings.”

“Blackmail?”

“I don’t think it was for America’s Funniest Home Videos. And someone wanted those tapes.”

Logan nodded slowly, his expression going from exasperated to pensive.

He wasn’t looking for his steak anymore.

“You know,” he said, “you’d actually make a pretty good cop.”

I snorted. I’d never heard that one before.

“I wouldn’t pass the background check,” I said. “So how’d you get into it? You don’t strike me as the usual cop material.”

“Oh? What kind of material am I?”

I looked him over.

Male model?

Actor?

Singer?

“Rodeo clown,” I said.

“Rodeo clown?”

“Yeah. Rodeo clown. You’re just as tough as the other cowboys, but you don’t feel the need to flaunt it.”

“Uhhh…thanks.”

“It’s a compliment.”

“I don’t know if my dad would say so. He’s the reason I’m a cop.”

“Let me guess: he was a cop.”

Logan nodded. “Arizona Highway Patrol.”

He was suddenly beaming at the thought of his old man. Just the slightest encouragement, I knew, and he’d tell me more, everything, his whole life story. It would take a while and it would have nothing to do with what I’d come to Berdache to accomplish.

Head junk, Biddle would have called it. Useless information.

I saw the waitress finally heading our way with our food.

My stomach started growling.

My soul was growling, too.

Feed me, they were both saying.

I smiled at Logan.

“Tell me about him,” I said.

The conversation was good. The food was good. Life felt good.

“Oh yeah—I meant to remind you,” Logan said as we left. “You really need to call the medical examiner’s office about your mother.”

Poof. Life felt like life again. Not so good.

“What’s there to talk about?” I said. “All they have to do is put a stake through her heart and bury her at a crossroads and that’s that.”

“Look, Alanis, I know how this works. You’re going to get stuck with the ashes and a bill for the cremation no matter what. You may as well have a say in how it all goes down.”

“You know what I did the one and only time I had a say in anything to do with my mother?”

“No.”

I opened my mouth.

I’d just spent the last thirty minutes hearing about Logan’s saintly cop father, and now I was about to say things about my mother that would make a sailor not just blush but sick to his stomach?

No. Not now. Not yet.

Maybe later…when I know you’re really ready, Josh Logan. When I know I’m really ready.

I forced myself to smile again.

“Thanks for lunch,” I said.

I went to the White Magic Five & Dime and spent the next two hours looking for jewelry and camcorder cassettes. I found dust bunnies, three fat rolls of hundred-dollar bills, and the bottle of Boone’s Farm Clarice had stashed in her underwear drawer.

And I found pictures. Seven of them, decades old, hidden in the pages of a Gideon Bible.

So my mother had looked back sometimes, too. She’d missed something. Longed for something. Felt something.

What do you know? She actually had a soul after all.

The pictures weren’t of me, though. Not one.

They were of Biddle.

Don’t fear the reaper, some tarot readers will tell you. The Death card doesn’t mean deadly dead death. It’s about letting go of the past and accepting—even embracing—whatever comes next. It’s about change, they say. And they’re not necessarily wrong. From alive to dead, though—that’s a pretty big damn change. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. And sometimes Death is just death.

Miss Chance, Infinite Roads to Knowing

Story time again.

It was 1986, and the girl, less little than ever, was standing in front of a mall multiplex in Cleveland, Ohio, thinking about the weird, weird film she’d just seen.

The weird, weird film wasn’t Big Trouble in Little China, which she’d also watched that day. That movie wasn’t weird. It was just goofy.

The weird, weird film wasn’t Labyrinth or Poltergeist 2, which she’d also watched. Those were just dumb.

The weird, weird film—the one she couldn’t wrap her adolescent mind around—was a surreal, disturbing yet oddly hypnotic science fiction fantasy called Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

She’d been at the mall all day. It was her babysitter.

Reading paperbacks in the B. Dalton had gotten her through a few hours. Change-raising every zombie-teen cashier in the food court had killed another while netting her enough money to buy a JC Penney necklace she didn’t really want and could have easily stolen anyway. With what she had left, she’d bought a ticket for Cobra and a bucket of popcorn and a jumbo Mountain Dew.

She always paid for the movie she least wanted to see. She felt bad for them. She was about to spend nine hours adrift, changing seats and screens and stories and realities at a whim. Yet she didn’t have ninety minutes for Sylvester Stallone as a leather-wearing criminal-killing cop? Poor guy. Here. Have $3.50. Buy yourself some shiny new bullets.

The girl had seen Ferris Bueller’s Day Off first because it was starting when she walked in and the guy from War Games was in it. It was a movie about kids who weren’t much older than

her, who lived in the same country as her, who had the same skin color and spoke the same language, yet beyond that it was utterly alien. It may as well have been the new Star Trek movie. The Search for Who-Knew-What on the strange new world of Suburbia.

These people went to a nice school. They had nice friends. They had their own nice rooms in their own nice homes. They had nice.

And they seemed to hate it. All they wanted was to escape from it. So they ran away to the city and had an adventure. An adventure with wacky mishaps and singing and dancing.

The girl knew about adventures in the city. She’d had a lot of them.

The mishaps weren’t wacky, and there was never any singing and dancing.

The first time she saw the movie, she hated it. Yet she found herself coming back to the same theater again and again, catching bits and pieces before sneaking off to see something else.

She ended the day with Ferris Bueller. And the last time he looked out into the audience after the credits and said, “You’re still here? It’s over. Go home!” she burst into tears, and she didn’t know why.

She made sure to dry her eyes before walking outside. Then she sat on the curb and waited.

The mall was closed. The parking lot was nearly empty. Before long, she was alone.

Biddle and the girl’s mother showed up after midnight. They were driving a silver Lincoln Town Car, brand-new. So brand-new it had never even been bought.

Biddle was wearing a tuxedo. The mother—she called herself Carol now—was in the kind of evening gown the lady dancers used to wear on Lawrence Welk. She had a big, bushy dome of over-teased ’80s hair to go with it. The hair was red. Clairol 108 Natural Reddish Blonde, actually. The girl had helped dye it four days before.

“Been waiting long?” Biddle said.

Before the girl could answer, Carol told her, “Don’t complain. You’re the one who wanted to get dropped off at the mall.”

“I’m not complaining,” the girl said.

She knew better than to ask about their day. Biddle would tell her later if he was in the mood. So she just sat in the back and breathed in the Newly Stolen Car Smell and rewound and replayed and rewound and replayed Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Bow bow, she thought. Chika chikAAAAA.

They were staying in a fancier hotel than usual. A big one, with a huge atrium lobby and glass elevators and chocolates on the pillows every day. The girl had no idea what Biddle and her mother were up to, but it had put them somewhere nice and she hadn’t been involved in any way.

That was as close to nice as things ever got. She told herself to appreciate it while she could.

She was looking forward to her chocolate.

When they walked into their room, two men were waiting there. They were in their forties, heavyset, one dark-haired, one bald.

They had guns.

The bald man touched a finger to his lips. “Shhh.”

The door, already closed again, was just five feet behind the girl. It could’ve been a mile. She knew she wouldn’t reach it in time if she tried.

“Aww, geez,” the other man said when he saw her. “Nobody mentioned a kid.”

“Who are you?” Biddle said.

Not “What’s going on?” Not “How dare you?” He didn’t sound happy, but he didn’t sound surprised or angry either.

It didn’t matter. The man with dark hair shoved his gun into his pants—he wasn’t the sort of pro to have a shoulder holster—and walked up to Biddle and punched him in the face.

Biddle stumbled sideways into the wall, his hands pressed to his nose.

“Ow,” the dark-haired man said, shaking his hand. “Don’t make me do that again.”

“The stomach, dummy, the stomach,” his friend told him. “Look—you made him bleed.”

The girl started to cry. It seemed like the thing to do.

“Shut up,” her mother said. She was standing very still, her eyes wide and dry.

“Clean yourself up, then we’re going,” the dark-haired man told Biddle. He glanced at the girl. “All of us.”

“Just leave her out of it, all right?” Biddle said. “She’s got nothing to do with anything.”

The dark-haired man remembered. He hit Biddle in the stomach this time.

They took the Town Car. The men with the guns sat in front. The dark-haired one drove. The bald one watched Biddle and Carol in the backseat. He made sure the girl sat between them.

“You’re not fast enough to jump out,” he told the grown-ups. “And even if you were, just think about who you’d be leaving behind.”

Still, the girl got ready to duck.

Biddle and Carol never moved, though. Twice, Biddle tried to talk, started to say “Look, guys—”

Both times the bald man brought up his hands. One held his gun. The other was putting a finger to his lips daintily, delicately. The second time, the gun was pointed at the girl.

Biddle stopped trying after that.

They drove out of the city, through the suburbs, into nowhere. The roads grew narrower and darker and more deserted.

They turned off onto a gravel driveway. Passed a farmhouse, passed a barn.

They stopped beside a field of tall green stalks. Corn in long, neat rows as straight as iron bars.

Another car was there already. It was big, boxy, ugly. Like the men standing beside it.

There were four of them. Biddle and Carol knew at least one.

“Shit,” Biddle said as the headlights swept over them.

“Don’t let him hurt my baby!” Carol howled. She threw her arms around her daughter. “We’re sorry! We’re sorry! Not my daughter! Please! Not my little girl!”

The men had to drag her out of the car. Biddle got out on his own. He started to say something to the girl before he left, but he thought better of it and just gave her hand a squeeze instead. He looked into her eyes in a way that seemed to say let this moment last forever. Only it didn’t, and he and Carol were taken out to the field, around one corner, out of sight.

The girl they left in the backseat. The bald man was told to stay and watch her.

“What am I, Mary Poppins?” he said.

But he seemed relieved.

Half a minute went by in silence. Then the girl heard sounds coming out of the darkness.

Pleading. Weeping. And laughter, too. A man’s laughter, joyless and cruel.

“Oh god oh god oh god,” the girl said. “No no no no no no.”

“Be quiet,” the bald man said. “Everything’s gonna be fine. They’re just talking.”

There was a scream, so brief the girl couldn’t tell if it had been Biddle or her mother.

“Oh god oh god oh god.”

“Be quiet,” the bald man said again. His voice wasn’t gentle but it wasn’t harsh. He looked like he wanted to be home in bed.

Something outside caught his eye, turned his head. The girl turned to look, too.

The dark-haired man was walking back toward the car with Carol. She was crying hysterically, staggering. The dark-haired man had to hold her up with both hands, guide her. His gun was stuck in his pants again.

The bald man opened the passenger-side door. The overhead light came on.

“What’s going on?” the bald man asked.

“She needs to talk to the kid.”

“What? You’re kidding.”

It was obvious the bald man had thought he’d never see the woman again.

“Oh, baby, baby, baby!” she sobbed when she saw the girl. Her knees buckled, and the dark-haired man barely managed to keep her on her feet.

“Roll down your window,” the bald man said to the girl.

She did as she was told.

“You’re okay, baby?” Carol said as she lurched toward the car. “No one’s touched you?”

“Oh, thank god. I just had to make sure you were all right. They say they won’t hurt you, they’ll let you go, if I tell them where I hid the—”

Carol’s knees went again, and she started to crumple.

“Goddamn it,” the dark-haired man said as he strained to keep her from falling.

And then there was a flash of light and a muffled pop and the man was falling backward.

Carol darted toward the car, no wobble to her knees now, and stuck the gun she’d just stolen from the dark-haired man into his bald friend’s face.

“Scoot over and drive or you’re dead,” she said. All trace of panic, desperation, emotion was gone from her voice. Her face was blank. A mask stamped out by a machine.

“I…I don’t have the keys.”

“Ohhhhh no,” the dark-haired man moaned as he rolled on the ground clutching his gut. “Ohhhhh no.”

Carol turned just long enough to shoot him again. Then she pointed the gun back at the bald man.

“They’re still in the ignition, asshole.”

“Hey!” someone shouted in the distance. “What the hell’s going on?”

The bald man got behind the wheel and started the car. Carol swung in beside him and slammed the door shut.

“Out to the road,” she said. “Not too fast and not too slow.”

The car started moving.

The girl looked out the back window. She could see hazy shapes moving in the gloom. There was another flash and for a split second she could see two men running after them. Something thumped into the back of the car.

“A little faster,” Carol said.

The bald man gave the car more gas. They shot onto the gravel drive, skidded, then straightened out and headed for the road.

“Wait!” the girl said. “What about Biddle?”

“Left at the end of the driveway,” her mother said. “Then hit the speed limit and stay there.”

“We can’t just leave him! We’ve got to go back!”

“Take the first turn you can. Right or left, it doesn’t matter.”

“Mom—”

“Are they following us?”

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

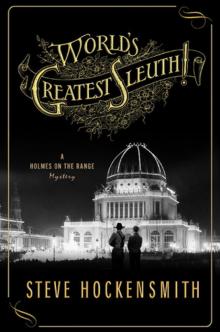

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!