- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

Dreadfully Ever After Page 16

Dreadfully Ever After Read online

Page 16

“However they got past the checkpoints,” she said, “it will be quite some time before any soldiers arrive to attend to them.”

Mr. Bennet shook his head. “The Shevingtons don’t fight dreadfuls, Lizzy. We shouldn’t involve ourselves.”

“Oh, Papa?” Kitty said. “I think we’re about to get involved.”

Papa Zombie apparently found ankles less than satisfying, and, rather than move on to the juicier flesh of the calf or thigh, it stood and started lurching toward the Bennets.

“We should run,” Mr. Bennet said.

“I will not run,” Elizabeth replied.

The dreadful was no more than forty paces away now, and it was gaining speed with each step.

“Really, Elizabeth,” Kitty said. “We should run.”

“I will not run.”

Papa Zombie opened its mouth and roared, and Mama Zombie, as if still playing the dutiful wife, dropped the gentleman’s head and staggered off after its mate.

“You should run,” Nezu said.

Elizabeth hadn’t even noticed the man slip up beside them. By the time she did, he was already off again, charging Papa Zombie. He started at a sprint and then flipped himself end over end—ninjas and their incessant hand springs!—until he was soaring into the air toward the unmentionable. At the apex of his flight, he pulled a katana from a back-scabbard hidden beneath his cutaway coat, and as he fell back to earth the blade bit into the dreadful’s head. It stopped slicing downward only when it had reached the creature’s collarbone, and the skull and neck split open like the blooming of some viscous red blossom. The zombie ran a few more staggering steps before pitching forward and tumbling, cleaved head over heels, along the cobblestones. It finally flopped to a stop at the Bennets’ feet.

Nezu, meanwhile, never slowed. His momentum carried him forward into another roll, and then he was sprinting and springing, springing and sprinting toward the other unmentionables. Mama Zombie he cut in half in his haste to reach the youngsters, who (in a display of the instinctive self-preservation that sometimes presented itself even in those with no more self to preserve) were retreating up the street. Once their heads were in the gutter, he could stroll back to the matriarch of the family at his leisure, and this he did with a casual calm and absolutely no sign that his acrobatics had winded him in the slightest. The zombress—or the top half of her, anyway—slithered toward him, hissing and clawing at his feet, but he was able to finish her off with an upward-arcing slice of the sword, not unlike a Scotsman swinging his “golf” club.

Watching him, Elizabeth had to respect the man’s formidable skills even as she resented that her own remained untapped.

“Well, I don’t know about you,” Kitty said, “but I’m impressed.”

She looked it, too. In fact, she was gazing at Nezu with such smiling delight, Elizabeth almost warned her not to applaud.

“Ooo,” Kitty cooed, “he is a marvel with Fukushuu.”

“Fukushuu?” her father asked.

Kitty nodded at Nezu and the sword he was resheathing as he walked toward them. “His katana. He told me it belonged to his father.”

Mr. Bennet looked around Kitty at Elizabeth.

She nodded. She knew what it meant. The word, anyway. Living with Fitzwilliam Darcy, how could she not have picked up a little Japanese?

Fukushuu meant “revenge.”

“Next time,” Nezu said as he swept passed them, “run.”

Behind him, long red fingers stretched out from puddles of blood, creeping their way toward the grates in the gutter and, below, the new sewers that ran under all of London.

CHAPTER 25

At first, Mary didn’t mind the stares. In fact, she rather relished them. So she was a lady walking through a respectable neighborhood beside two mangy dogs and a black box. What of it? She could choose her own company. If she should decide to go for a stroll with a flock of geese while pushing an orangutan in a purple perambulator, who had the right to stand in judgment?

She had released herself from the shackles of propriety. She was free!

Still, the gentlemen’s frowns, the ladies’ scowls, the children pointing and laughing—she wasn’t entirely immune to it. There was freedom, and then there was making a spectacle of oneself.

So Mary tamped down her misgivings and kept up her nerve the best way she knew how.

“Mary Wollstonecraft tells us,” she said, “and I quote: ‘Women are systematically degraded by receiving the trivial attentions which men think it manly to pay to the sex, when, in fact, men are insultingly supporting their own superiority.’ How true! It is one of the reasons I have never much missed such attentions. If one is pursued by suitors, let’s say, is that really a thing to be envied? For what is the purpose of pursuit but capture, imprisonment, destruction even? Better, I think, to be left alone to one’s own pursuits—those that elevate spirit, mind, and body—rather than wallow in sentiment.”

Here, Mary remembered to pause (something she’d been mostly forgetting that morning) to allow Mr. Quayle the opportunity to either demonstrate his intelligence by agreeing or expose his ignorance by dissenting. She heard nothing from the little crate rolling along beside her, and after a moment she began to wonder if Mr. Quayle had been listening at all—or was even awake. Ell and Arr certainly seemed to know the way, turning crisply at all the right corners without any apparent pulling on the reins that disappeared into the slot of Mr. Quayle’s box. For all Mary knew, the man inside was slumped against a pillow, snoring contentedly until a yap from his dogs alerted him that they’d reached their destination.

So she decided to try a test. She would ask the question her mother always claimed either put men to sleep or sent them fleeing.

“Have you ever read Mrs. Wollstonecraft?”

“I mean”—she quickly threw in before Mr. Quayle could answer (or not)—“did you ever read her? Before your … change in circumstances?”

“Oh, I still manage to keep up my reading,” Mr. Quayle replied, sounding as chirpy and cheerful as one could when speaking (it seemed from the rasp of it) through a throatful of scars and sand. “I’ve trained Arr and Ell to shave my face, load a flintlock, and prepare and cook an entirely satisfactory shepherd’s pie. Turning the pages of a book was nothing. Yet I have, alas, never sampled Mrs. Wollstonecraft. I recently read her daughter’s novel, though.”

“Oh,” Mary said. “That. Yes, I read it as well. Mrs. Wollstonecraft died soon after giving birth to Mrs. Shelley, you know. I wanted to see what her sacrifice had begat.”

“I take it from your tone that you did not find Mrs. Shelley’s work worthy of her heritage.”

“Most novels are worthless, Mr. Quayle. Frankenstein has the added defect of being perverse. I can only take solace from the fact that Mrs. Shelley’s little grotesquerie will soon be forgotten, allowing her mother’s legacy to live on, unsullied and immortal.”

Mary almost stopped there, pronouncement complete, but she was overcome by the sudden urge to add four more words she had, up to then, rarely spoken.

“What do you think?”

“I’m afraid I must differ. The story aroused my sympathies in the deepest way imaginable. Though, thanks perhaps to my unique ‘circumstances,’ those sympathies often lay with the monster, not its creator. As to the book’s perversity, yes, I will grant it was intended to shock, in some ways. But, given the things you and I have seen—”

Mr. Quayle’s voice trailed off, and for a moment he fell silent.

“I found it quite diverting,” he finally finished.

“Ahh, but a book should do more than divert!” Mary declared. “It should do the opposite, in fact. It should focus one’s consideration on that which is real and important. It should strive for uplift. Inspiration.”

“I try to take those things from life, Miss Bennet. It has not been easy, I grant you … though of late I find I’ve had a bit more success than in years past. And here we are.”

They’d arrived at t

he gateway from Eleven to Twelve Central. When they tried to walk through, however, the soldiers there—the same ones who’d let Mary pass without any questions about her intentions (or sanity) a mere twenty-four hours before—looked tense and sweaty. The captain of the guard came over to ask if she and Mr. Quayle really, truly, absolutely, without question, no matter the consequences, being duly forewarned and absolving him of all responsibility, had to keep going.

Mary said yes.

“All right, then,” the man mumbled with a twitchy nod. “But I’d stay close to the soldiers, if I were you.”

“Soldiers?” Mary asked. The officer had already turned his back and stalked off, however, as if suddenly anxious to wash his hands.

On the other side of the gate, they found a crowd of clamoring, shabbily dressed people pressed around a squad of soldiers stretched along the roadway. Mr. Quayle had to set Ell and Arr to growling and barking to clear a path through the throng.

“You’ve got to let me out!” a man was roaring at the soldiers as Mary moved past. He lifted up a wailing baby swaddled in a canvas sack. “For my wee one’s sake! She needs a doctor!”

“I don’t know who you got that from, Coogan,” replied a soldier wearing a sergeant’s chevrons, “but you may as well take it back and get a refund, because you’re not getting through this gate.”

“You can’t do this!” another man shouted, and others joined in with, “For God’s sake!” “It’s an outrage!” and the like.

“This is the last time I’m saying it!” the sergeant bellowed back. “New orders. No one gets out without work papers. But don’t get your pantaloons in a bunch! Once the recoronation’s over, everything’ll get back to normal.”

“With one difference,” Coogan said over the squawks of “his” wee one. “We’ll all be dead!”

“And who liked ‘normal,’ anyway?” a woman threw in.

“Yeah!” half a dozen others called out.

A dark-skinned man wearing a red turban and an immense black beard turned and glared at Mary just as she cleared the edge of the crowd. It wasn’t often one saw foreigners in England anymore, for who would come willingly to the Land of the Dead? The fact that most proved immune to the strange plague only made them more resented in a country that was never particularly fond of outsiders to begin with. What remained of the old immigrant populations was rarely seen outside deepest London.

“And how about her?” the man asked in a heavily accented singsong, and he stabbed a finger at Mary. “Will you be asking the lady and her pets for papers when they want to leave? I think not! They’ll be free to come and go while the likes of us stay trapped in here like rats.”

The soldier who’d been doing all the talking waded into the mob and drove the butt of his Brown Bess into the outlander’s stomach.

“Keep a civil tongue and don’t forget your place.” The sergeant turned toward Mary as the bearded man doubled up in pain beside him. “I do apologize for that, Miss. All sorts of unpleasantness you’re bound to encounter here today. Even more so than the usual, I mean. You won’t be staying long, will you?”

“Just long enough,” Mary called back, and she and Mr. Quayle and the dogs carried on up the street.

The unpleasantness they’d been promised presented itself quickly enough: More bodies had been left out for collection, the heaps reaching as high as Mary’s chest in spots, and here and there soldiers worked in teams of two, collecting the heads of the dead and the dead-ish with heavy sabers. Even where the corpses were starting to get frisky, the soldiers never fired a shot. Instead, one would pin the stricken in place with a bayonet or pike while his partner finished the job with his sword. The practice conserved powder and musket balls, of course, but Mary suspected that wasn’t the only reason for it.

The walls would spare respectable London the sight of an epidemic, but even stones and mortar twenty-five feet high couldn’t blot out the sound of so much gunfire.

“We were lucky to get in … depending upon one’s definition of ‘lucky,’ ” Mr. Quayle said. “Tomorrow, without doubt, the quarantine will be total. No one in or out.”

“Agreed. Which makes it all the more imperative that we act immediately.”

“Agreed.”

They turned a corner and found themselves moving up a street that had yet to see its morning visit from the soldiers and body wagons. The locals had done what they could with their Zed rods, and the cobblestones were coated with fresh-pulped brains and bits of shattered bone. Still, there were stirrings in several of the corpse heaps, and Ell and Arr slowed and bared their teeth and growled.

“This is intolerable,” Mary said. “How could they allow it to become this bad?”

“Of which ‘they’ do you speak?”

“The authorities, of course. The government.”

Mr. Quayle’s box let out a little squeak.

“That was a shrug, Miss Bennet,” Mr. Quayle said. “Of the cynical, world-weary variety. Section Twelve Central and all such sections like it will always be tolerated, no matter how appalling they become, because it is easy to tolerate that which one ignores. And, at the moment, the authorities—and those who keep them in power—have all the more reason to focus their attentions elsewhere. There is a king to be recrowned. There are balls and banquets and jubilees to plan. The only thing that would be intolerable would be spoiling the fun.”

Mary looked down at the box rolling along the blood-slimed street and wondered, not for the first time, what the man inside it looked like.

“You have a didactic streak, Mr. Quayle,” she said.

“My apologies.”

“You misunderstand me,” Mary said, and for perhaps the first time in her adult life, she gave in to an impulse: She rested a hand atop Mr. Quayle’s box, the fingers spread wide. “I meant that as a compliment.”

“Ah. It has been so long since I received one, I failed to recognize it for what it was.”

Mr. Quayle’s voice was even gruffer than usual, and for a long while the only sound that came from his box was the rumbling of the wheels over the cobblestones.

Eventually, they reached the abandoned brewery Mr. Quayle preferred when keeping watch on Bedlam.

“It offers more seclusion than the alleyway you used for your observations yesterday,” he explained as they made their way past cobweb-covered casks and vast copper vats streaked with grungy green. “A kidsman and his gang of thieves have claimed the place as their den, but they shan’t disturb us. We came to an understanding long ago, they and I.”

“That understanding being …?”

“That if I am left to my business, they are left to theirs, including the business of breathing.”

“A happy arrangement for all.”

“Quite.”

“One thing puzzles me, however.”

They stopped in front of a staircase leading up to a walkway lined with shattered windows. Long wooden boards had been placed end to end from the bottom of the stairs to the top, creating a convenient gangplank for Mr. Quayle. Above, more boards led to a crate placed by a window that, Mary assumed, afforded the best view of the hospital grounds.

“Nezu told us that Lady Catherine’s ninjas have attempted to infiltrate Bethlem in the past,” Mary said. “And here I find that you have a cozy observation post that has seen no little use. Yet Mr. Darcy was tainted with the strange plague only two weeks ago.”

“You wonder why Her Ladyship would take such an interest in Sir Angus MacFarquhar before her nephew was infected.”

“I do, indeed.”

“I have wondered the same thing. My mistress has not seen fit to tell me, however. Nor have I felt quite suicidal enough to ask.”

Ell and Arr joined the conversation now, growling in harmony as they raised their wet black noses and snuffled at the brewery’s musty air. Mary copied them (minus the growling), tilting back her head and sucking in a long, deep breath through flaring nostrils, as Master Liu had once taught her. (“You cannot taste

what is on the wind with a dainty sniff. You must fill your throat, your lungs, your whole being! Now try again—with these crickets up your nose this time.”) The fetid stench of rotting wood and yeast and barley lay like a waterlogged blanket over every other scent, however, and Mary could smell nothing else.

After a moment, she began to hear. It started as a rustling sound and then became a scraping and pawing, all of it strangely echoey and metallic.

Mary looked at the top of the farthest beer vat just as a pair of hands appeared there. Rising between them came the scowling face of a sunken-eyed child. The boy hauled himself over the side and dropped to the floor, and within seconds more came spilling out after him, as though the vat were a cauldron boiling over with angry, rag-wrapped children.

Ell and Arr wheeled around to face them, snarling and snapping.

“Solomon! Solomon, where are you?” Mr. Quayle shouted. “Come out and call off your dogs, and I shall call off mine!”

“I think your understanding with Mr. Solomon is no longer in effect,” Mary said, “for his wards are now beyond any understanding at all.”

Another boy came crashing to the floorboards with what looked like a large reticule in one hand. It was, in fact, a man’s head, clutched by the long grey beard that grew from the pain-contorted face. The eyes were rolled back in their sockets to point at a smashed crown dripping blood and morsels of brain.

“Mr. Solomon?” Mary asked.

“Mr. Solomon,” Mr. Quayle replied.

The cholera had swept through the thieves’ crib, it seemed, and now Mr. Solomon’s gang was interested less in picking pockets than in emptying skulls.

The boys were already loping forward toward the intruders/buffet.

“MR. SOLOMON’S GANG WAS LESS INTERESTED IN PICKING POCKETS THAN EMPTYING SKULLS.”

“Let’s see if this drives off the little guttersnipes,” Mr. Quayle said, and at a cluck of his tongue Ell and Arr slipped from their harness and stepped aside.

A panel opened near the base of Mr. Quayle’s box, and a long dark tube slid out.

“Very impressive,” Mary said.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

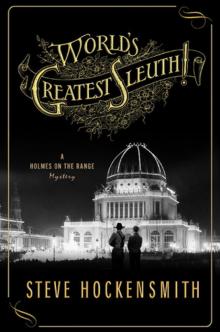

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!