- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

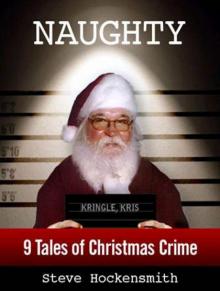

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Page 2

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Read online

Page 2

As a serious, marinara-in-her-veins Italian-American, Connie had to try very hard not to be offended. She had to try even harder when she tasted it.

Bud, it appeared, hadn't done much cooking in his life. He didn't seem to know the difference between garlic powder and cumin, for instance. And ketchup and tomato sauce were considered interchangeable. Somehow, Connie kept a smile on her face even as she choked down the man's blasphemous culinary abomination.

When Bud came by a few days later with something he called a "Velveeta sausage log," Connie let him know she wasn't hungry just then but she sure was looking forward to a heaping plate later on. Over the next week, she transferred one hearty slice a day from the refrigerator to the bottom of the garbage can.

Given her earlier encounters with Bud's kitchen experiments, Connie was in no hurry to chomp into the man's first stab at cake baking. She'd always found the pleasures of fruitcake to be fickle and fleeting under the best of circumstances. A Bud Schmidt fruitcake could be dangerous.

So Connie gave the cake a place of honor amongst the cookies and biscotti and chocolate balls sent down by her relatives up north, but she never took a bite. She only mentioned the fruitcake to Bud once, fearful that he would suggest brewing up some coffee and tucking in.

"Thanks for your little surprise," she told him. "It's lovely."

Bud smiled and gave her an "Awww shucks, it was nothing" shrug. He thought she was talking about the Velveeta sausage log. Or maybe something else he'd done. His memory wasn't what it used to be. And anyway, forty-three years of marriage had taught him not to question a woman's gratitude. If it's something you earned, great. If it's not something you earned, even better.

Over the next week, the mountain of holiday treats in Connie's kitchen was gradually worn away by the erosion of near-constant snacking. Yet the fruitcake remained, inviolate, untouchable, like some moist and mysterious monolith.

It had to go.

Connie couldn't just throw it away, though. It was a symbol of Bud's devotion . . . though, in all likelihood, a spectacularly nasty one.

So instead of tossing it out, she dressed it up. She plated it with candy armor— gumdrops and Skittles along the sides, peppermints and candy canes on top. When she was done, the fruitcake was unrecognizable.

She covered it in Saran Wrap and walked it to the trailer of Always Sunny's most hated resident: George "Bones" Heaton, the manager. She felt a little guilty about pawning off someone else's gift as one of her own. But wasn't there an old legend that there's really only one fruitcake in the world—it just keeps getting passed around? Who was she to stand in the way of tradition?

* * *

Bones (short for "Skin and . . .") was a small, grizzled man with a large, fleshy mouth that spewed ill will like a smokestack. Always Sunny's residents were not, on the whole, a rowdy or unreliable bunch. So Bones spent very little of his time breaking up wild parties or overseeing evictions. Instead, his duties as manager leaned heavily toward maintenance work and general handymanery.

As undemanding as these chores generally were, however, Bones seemed bound by holy oath to make them as unpleasant as possible for all concerned. His rote response to any complaint, large or small, were the words "Whadaya want me to do about it?"

Even if you told him exactly what you wanted him to do, the odds weren't good that Bones would actually do it. Your chances for success worsened considerably if you got on his bad side somehow—which was easy to do, since his "bad side" comprised the majority of his being.

In December, there were two sure-fire ways to inspire his wrathful sloth: (A) coming to his door singing Christmas carols or (B) not coming to his door with a present. Bones had been known to chase away suddenly-not-so-merry carolers with a garden hose. Gifts, on the other hand, he accepted greedily, if not graciously.

Her new neighbors had let Connie know that a Christmas offering to Bones was mandatory. Connie was, of course, outraged and offended. But she also had cracks in her driveway and a box elder that was growing perilously close to her telephone line. So she brought Bones a gift.

"Huh," the little man grunted when he saw it. "You say there's a cake under all that candy?"

Connie came as close as she could to a good-natured laugh. "Oh, yes. It should be a tasty one, too. I had my niece Gina make it for me. She's a pastry chef up in New York. A real wiz kid with the baking. Sometimes she gets kind of fancy with the ingredients . . . you know, experimental. But she—"

"Yeah, okay, thanks," Bones said, signaling that Connie's audience with him was at an end. The door to his trailer was closed before she could finish her farewell "Merry Christmas!"

Later that day, Bones's wife Virgie found the fruitcake on the kitchen table when she returned from the latest meeting of her divorce support group. She'd never been divorced before. She was just trying it on for size. After four weeks with the group, she still couldn't figure out what everyone was complaining about.

"What's this?" she called out.

Bones was in the living room, approximately twelve feet away, watching Judge Judy dole out justice reality-TV style.

"What's what?" he hollered back.

"This thing with all the crap on it!"

"What?"

"This hunk of crud in the kitchen!"

"I don't know what you're talking about!"

"This weird-lookin' blob on the counter!"

"That's a fruitcake!"

"A what?"

"A frrrrruitcaaaake!"

A fruitcake? Virgie thought it looked more like a candy-encrusted brick.

"Where'd it come from?"

It took five more minutes of yelling to work out the details. Virgie never left the kitchen, and Bones never left his seat.

When it was all over, Virgie took the fruitcake to its new home. She thought the cake looked more decorative than edible, so she placed it amongst the snow globes, nutcrackers and miniature angels on the mantelpiece of the double-wide trailer's faux fireplace. There it stayed for the next twelve months.

Virgie and Bones usually packed up their Christmas decorations around Valentine's Day or, at the very latest, Easter. But this year it became a one-man job—and the man in question was reluctant to commit to any project that required him to put down the remote control.

When Virgie left Bones, she chose the timing carefully. She didn't want a big fuss. So she started packing her bags five seconds after the kick-off of the Super Bowl. She was out of the trailer by half-time. Bones tracked her down the next day to attempt a reconciliation—over the phone.

"Awww, you don't care if I'm there or not, George," Virgie told him. "I bet you didn't even stop watching the game after I left last night."

"Well, yeah," Bones admitted sheepishly. On the widescreen TV a few feet before him, Judge Judy was scolding a man for selling his best friend a sickly parrot. "But I didn't enjoy it."

The reconciliation did not take root, and Bones found himself single for the first time in fifteen years. It didn't really affect his life much, except that there was a lot less shouting around the trailer and no more bickering about what to watch on TV.

* * *

The following November, Bones's bachelorhood produced an unexpected dividend. Through no effort of his own, the man suddenly found himself with an admirer.

Ethel Queenan began dropping by every day with food.

"That wife of yours never fed you right," she'd say as she handed him the latest creation from the pages of her new cookbook: Bake Until Bubbly!. "And now that she's gone, you're just wasting away to nothing."

In attempting to seduce Bones Heaton with fiesta chicken and tuna noodle strudel, Ethel knew she'd scraped all the way through the bottom of the barrel deep into the dirt beneath. She was desperate.

Whether Connie Sandrelli didn't care for fruitcake or simply had a cast-iron stomach, Ethel would never know. But the man-stealing hussy not only survived the holiday season, she married Bud Schmidt just a few months later. To show that there

were no hard feelings, Ethel baked them a chocolate cake—or, to be more precise, a chocolate, Clorox, Cascade, Tide and lemon-fresh Pledge cake. The resulting black sludge was so noxious with chemicals Ethel had to throw it out, pan and all. She nearly passed out from the fumes.

Only two more Always Sunny men came on the market after that. One died three weeks after his wife's funeral. The other moved to San Francisco with his wife's brother, something he'd apparently been waiting forty years to do.

That made Bones Heaton the only unattached male in the trailer park. He was a little too young and a lot too lazy, but he was eligible, and Ethel needed a husband. For her, being single was simply not an option. Take the "man" out of "woman" and all you've got's a "wo," her mother used to say. Ethel always assumed this was a firm endorsement of matrimony. She had no intention of being a "wo" the rest of her life.

Bones accepted her attentions with uncharacteristic patience, largely because he'd grown sick of frozen pizza and fish sticks. Like Bud Schmidt before him, he never invited Ethel inside or dropped by her trailer in return. But he never chased her away with the garden hose, either. In fact, as Christmas drew closer, he began to worry that she'd give up on him before his refrigerator was fully stocked. Given the trailer park's demographics, it was only a matter of time before another Always Sunny widower stepped onto the auction block. And Bones was realistic enough about his personal charms to know what would happen if he faced competition.

What was called for was a Christmas gift. But Bones being Bones, it would have to entail minimum effort to procure. Ideally, it would be something he could find within ten steps of his La-Z-Boy.

Which is how it came to be that one warm December evening Bones Heaton presented to Ethel Queenan a beautifully decorated, twelve-month-old fruitcake. Ethel cooed and made a fuss over it, though it actually looked far too gussied up for her tastes. But the man had made an effort on her behalf, and that boded well.

And anyway, Ethel thought as she walked back to her trailer, peel off the peppermints and the thing was probably perfectly fine.

She'd been cooking all afternoon, and she was hungry.

I KILLED SANTA CLAUS

After Christmas break, everyone in the dorm was talking about what they did over the holidays. People were like, "I watched 22 movies" and "I went to Cancun" and "I smoked a lot of pot, man."

When I got asked what I did, I'd say, "I killed Santa Claus." Which would get a polite ha ha. And then I'd say, "No, really. I'm not kidding." And then I'd tell the story.

Before long, people were coming up to me all over campus saying, "Are you that Santa-killing chick?" I was famous. Or maybe infamous. It was pretty cool—for, like, a week. Then I got sick of telling people about it over and over again. I mean, it's a pretty long story. So after a while when people came up and said, "Did you kill Santa Claus?" I'd say, "Sorry, you've got me confused with someone else. I killed the Easter Bunny."

But I guess I could tell the story one more time. After that, I'm going to retire it. I won't tell it again till I've got kids I need to scare into line. "Don't mess with your mother, Timmy. She offed St. Nick."

My own mom, she believes in the importance of work. For everybody. All the time. So one of the joys of coming home from school is finding out what sucky job she's got lined up for me. During my first summer break, I worked for the dog census. You walk around to people's houses—or, in some of the neighborhoods I went to, trailers—and ask if they have a dog and, if so, does Fido have a license? Tons of fun, let me tell you. There's no better use for a cheery summer afternoon than asking Cletus the Slack-Jawed Yokel if his mutt is registered with the county. And all for minimum wage. Thanks, Mom!

Christmas two years ago, I wrapped presents at J.C. Penney until my fingers bled. The summer after that, I went back to the dogs. Come the next Christmas, I was a squirter, chasing people around Dillard's with a perfume bottle. Then, for the summer, I worked a cash register at Chuck E. Cheese...an experience I plan to talk to a therapist about, as soon as I can afford one. Hell isn't other people. It's hearing an animatronic ostrich sing "Wind Beneath My Wings" 50 times a day.

So finally I reach the Christmas break of my senior year—my last chance to kick back and truly chill without worrying about finding a job or a place to live or any of that "real world" stuff I'm looking forward to soooooooo much. But does my mom give me a break and let me spend my vacation doing what I want to do—suck candy canes and watch TV? Of course not. Instead, I get The Speech.

"When your father ran off with that woman," it begins, "he left us to fend for ourselves. We don't have it easy. We can't sit around eating bonbons. We've got to roll up our sleeves and get our hands dirty. That's exactly what I've done. I have worked hard—very hard—to keep this house and put food on the table and send you to college. But I can't do it alone. You've got to take some responsibility and chip in and — "

Yada yada yada, as they say.

After a few minutes of this lecture, all of which I know by heart, I said the only thing that can bring it to an end, which is, "You're absolutely right, Mother. How could I be so selfish? Please tell me what [mind-numbingly tedious minimum wage] job you've found for me."

My mom smiled and said, "This one's going to be fun, Hannah," which sent a chill down my spine. If my mother thinks it's "fun," I figured, it's got to suck big-time.

And I was right.

"You remember Missy Widgitz, Mark Widgitz's mother," Mom said, referring to two people I have absolutely never heard of. "She just became the promotions director over at Olde Towne Mall. She's got a holiday position that would be perfect for you."

I sighed and said, "Great. Gift wrapping. I'll go get the Band-Aids."

Mom laughed—another ominous sign. "No, it's a lot better than that. They lost one of their elves."

There was a long pause, during which my mother stared at me with this big, goofy grin, waiting for me to say something upbeat like, "Wow! Really? What great news, Mom!" But I was confused.

"Lost...an elf?" I said. "What? They want me to help find it?"

Mom laughed again. it's nice to know I can provide her with so much cheap amusement.

"No, no. They need an elf for Santa's Workshop."

I was still thinking I was supposed to be an Elf Wrangler, which doesn't make any sense, when it dawned on me.

You're the elf.

My blood ran cold.

"You start tomorrow," my mother said.

I slit my wrists and threw myself off the roof.

O.K., I didn't. But maybe I should have. Instead, I showed up at Olde Towne Mall the next day and reported for elf duty.

Here's what you need to know about Olde Towne Mall: When they say "Olde," they're not kidding. In fact, "Ye Olde Crappie Mall" would be a better name for the place. It's what used to pass for a shopping mall back in the seventies, before River City got a real mall. It's all gray tile and florescent lighting and fake plants and rednecks. The nicest store they've got is Sears.

At the exact center of this dump was the horrifying torture chamber otherwise known as Santa's Workshop. You know the drill: plywood house, plastic candy canes, mechanical reindeer, fake snow, fake everything. And the biggest fake of all sat on a throne lording over it all. Santa Claus. Or, as I came to know him, Big Buck.

Big Buck was not one of those professional Santa types you read about who grow their own beards and love children and act like playing St. Nick is a role worthy of De Niro. Big Buck wore a phony white beard that was always a little bit crooked from being yanked by the screaming kids he obviously loathed. And he didn't smell like peppermint and warm cookies, the way you think Santa should. He smelled like sweat and cigarettes and Pabst Blue Ribbon. And his deep-fried drawl was all wrong, too: Last time I checked, the North Pole is not south of the Mason-Dixon.

But at least his belly was real. And he laughed really loud. And he liked to sneak into people's homes at night. I didn't learn that last bit till later, though.

B

ig Buck had a love-hate thing going with me at first. Or I should say a lust-hate thing. I was the only female elf, which would've been bad enough without the costume I had to wear: red tights, a green felt smock and a red stocking cap, all about two sizes too small. I could barely squeeze into any of it. I was like a felt-wrapped sausage.

This led to a lot of ogling from both Big Buck and a disgustingly high percentage of the dads I had to deal with. I was the greeter elf, the one in charge of maintaining order in the line of supplicants to King Claus. When Junior's time came, I'd walk him up the path to the stairs in front of Santa's throne. Then I'd go back to the head of the line to make sure mom and dad didn't spoil this special moment by getting too close. Another elf—Arlo Hettle, a slumming college kid like me—would step up and take a picture of Junior and Big Buck with an instant camera. Then the third and final elf, a rat-faced little troll named Kev Kane, would hustle Junior away while I brought up the next kid. I found it deeply depressing that Kev was as old as me and Arlo put together. If I was still elfing when I hit 40, I'd hang myself with a string of garland.

Still, I've got to say it: I was a natural . . . at the kid-herding part, if not being holly-jolly. Within an hour, I had the moves down so pat—collect child, step step step, leave child, step step step, repeat—I could've done them with my eyes closed. Which left me free to notice things like the come-hither looks Big Buck kept giving me. The really creepy thing, though, was the way he'd spaz out if I came too hither at the wrong moment.

"Y'see that gingerbread man there?" he snapped at me after I brought up Kid #48 of the day while Kid #47 was still on his lap. "I don't ever wanna see you or anybody else on my side of that while I'm talkin' to a youngster."

"O.K.," I said, thinking, "Youngster"? You look at them like they're cockroaches.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

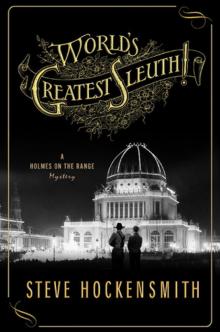

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!