- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

Holmes on the Range Page 21

Holmes on the Range Read online

Page 21

“Why would he come all the way out here?”

“Only one way to find out,” Old Red said, and he got Sugar going before I could slow him down with more talk.

We were able to make good speed, for there was no science to staying on the trail. It took us far deeper into the VR’s grazing land than we’d ever been before, and we rode across open range and up and down gently sloping hills that would have made for pleasant riding if I hadn’t been worried about someone putting lead in our livers. Following the buggy tracks kept us exposed to view, making us easy targets for any unfriendly fellow with a Winchester in his scabbard.

Though the wind was at our backs, I eventually began to sense by way of my nose that we would soon be in the company of cattle. We found them not long afterward, perhaps a thousand strong. They were meandering unattended across a long, narrow strip of grassland at the bottom of a rocky punch bowl formed by the surrounding bluffs. From the way the grass had been flattened throughout the valley, it was clear they’d been packed in pretty tight. The Duke’s party seemed to have taken pains to drive straight through the center of the herd, and many a cow pie had been squashed beneath buggy wheel and horse’s hoof.

At the far end of the valley, a stand of trees ringed a largish pond around and in which perhaps fifty cows were cooling themselves. It appeared that this modest prairie oasis held some appeal for one of the VR’s two-legged residents, as well, for the trail split here—one set of buggy ruts cut straight over to the pond, while the other kept on to the south, out of the valley. Gustav eased his horse to a halt where the trails separated.

“The tracks down to the water must be from Edwards today,” I said. “The trail’s fresher. The patties it runs through ain’t even baked hard yet.”

I had no doubt my brother had already noticed that. I just didn’t want him thinking I hadn’t. He acknowledged my trail-reading with a nod, then unhorsed himself.

“Hold on to Sugar. I wanna look at somethin’.”

I dismounted and stood there holding the horses. They wished to get at that water, but Old Red didn’t want them mussing up the ground before he’d had a chance to look it over. He followed the buggy tracks to the pond, walking so bent-over his face would’ve been dead even with the buckle of his gunbelt had he been wearing one. It was pure luck that kept him from charging hat-first into a heifer’s hindquarters, as he didn’t look up to make sure the cows were clearing out of his way. When he got about ten feet from the water’s edge, he dropped down to one knee.

“What ya got, Brother?”

“Footprints,” Gustav said. “Cows’ve already made a mess of ‘em, but . . .” He crawled closer to the marshy muck that ringed the pool. “Edwards took himself a little stroll down to the water here.” Old Red hopped up and planted his feet firmly in place. “This is as close as he got. Didn’t want to muddy his pretty shoes, I reckon.”

My brother stayed there staring out over the water. Several cows stared back at him.

“Then what?” I asked.

“Then he left. Got in the buggy, wheeled around, and headed back to the castle.”

“Well, it’s plain to see why he’d go to such trouble to visit a spot like this.” I nodded at the murky brown water and the poop-pocked ring of hoof-trampled mud that encircled it. “This here’s a regular Garden of Eden.”

“Yeah,” Old Red said, slapping away some little winged pest that was making a run at his neck. “Only things that’d wanna picnic around here are horseflies and mosquitoes.”

“So why do you think Edwards really came back here? To meet somebody maybe?”

“Nope. No other tracks.”

“You can’t tell me he came all the way out here to eat cheese and bread with a bunch of cows.”

“I ain’t tellin’ you nothin’, Brother. I don’t have anything to tell—not till I’ve had a chance to do some serious thinkin’.”

Gustav picked up a clod of dirt and threw it out into the pond. He spent a moment just watching the ripples spread before he turned and spoke again.

“Alright—you can let the ponies get ‘em a taste now.”

I dropped the reins, and Sugar and Brick hurried over and dipped their muzzles in the pond.

“Don’t drink too deep,” Gustav said, giving Sugar’s haunch a friendly pat. “We got a lot of ridin’ yet to do today.” He peered off to the northwest—back the way we’d come.

“Anybody followin’ us?” I asked, not bothering to pretend I had eyes as sharp as his.

“A few somebodys,” Old Red said. “Not that I see ‘em yet. I don’t. That won’t last forever, though.”

“You think they’ll figure out we ain’t gone to Miles?”

“Not if we’re lucky. But I ask you—when was the last time an Amlingmeyer got lucky?”

I pondered on that a moment before speaking again.

“We best get movin’.”

We let the horses ease back into their work, heading up out of the valley at a canter. As we crested the far ridge of the punch bowl, the valley beyond popped into view—as did a dark line that cut across it.

“Hel-lo!” Gustav said.

He was greeting another clue—or a little nest of them, more like.

That dark line was barbed wire, and the buggy tracks headed straight for it. A thin plume of gray smoke wound its way skyward from the other side of the fence.

Deep in the VR’s most forbidden corner, someone was cooking dinner.

Thirty

THE BEAST

Or, We Discover the Bar VR’s Secret—and the Secret Discovers Us

The territory we were moving into lacked the smooth flatness of the valley we’d just left, and rolling hills and rocky bluffs soon blocked our view of what lay ahead. In addition, late-afternoon was turning to dusk as we rode, and each minute stole from us a bit more light by which to follow the trail. It was easy enough to find the gate through which the buggy had passed, however, and Old Red opened it up and waved me through.

Once on the other side, heaping turds and hoofprints soon dotted our path, and as we approached a particularly steep hill each became more abundant. The tracks, in fact, grew so heavy it got to looking like a herd two thousand strong had recently rolled through on the run.

The buggy ruts we’d been following led up to a rocky bluff nearby. There they stopped, though the hill didn’t round off for another thirty feet or so. Down below, the cattle tracks wound snug around the base of the hill.

“It almost looks like the Duke and his pals had a front-row seat for a stampede,” I said.

“Why almost? I think they did.” And with that Old Red gave Sugar his heels and steered the horse over to where the stampede—if that’s what it had been—had kicked up a band of turf about a hundred feet across. When we reached the cattle trail, my brother got to riding along it.

Now when a herd gets spooked, there’s no figuring which way that avalanche of beef will tumble, which is why so many punchers pass through the pearly gates looking like strawberry jam. All the same, there’s one thing you can count on cattle not doing without being pushed to it, and that’s circle up.

Yet that was precisely what had happened here. That trail hooked right and hooked right and just kept on hooking right until it brought us all the way around the hill to the spot we’d started from. As we finished our little ride on the merry-go-round, Gustav bent over practically double in his saddle. I thought he was looking for more clues amongst the dirt until his giggles worked themselves up into guffaws. I couldn’t join in, as I had no idea what the funny was in the first place.

“Uly brought the Duke and the rest of ‘em all the way out here just so they could watch a bunch of cows run around a hill?” I asked.

Old Red’s cackling wound down into mere snickering, and he drew in a deep breath and sighed with the satisfaction of a man who’s just enjoyed a choice steak after a week of jerky. “You might say that.”

“I did say it. Now why don’t you explain it?”

My brother nodded, happy to oblige for once.

“There’s an old trick the Sioux used to pull. Or maybe it was the Cheyenne. Or the Apache. Depends on who you hear tell it. Anyway, they might have twenty warriors in a raidin’ party, but they could make it look like a hundred and twenty if they got some troopers pinned down in the right spot—a box or blind of some kind. The braves would get to ridin’ circles around them bluecoats until there was no way a man could keep track of the numbers. Used to scare the crap out of them poor army fellers. It looks to me like the McPhersons pulled the same trick. They got the Duke and the others up on the bluff and then they ran a few hundred critters around in so many circles they looked like a river of cattle instead of a mere trickle.”

“Now wait a second,” I said. “It’s plain enough Uly’s boys salted the trail down here with herds to give the Duke and them others the impression the spread’s overflowin’ with beef. Alright. Makes sense. But why the show here? What would this do that the ride down didn’t?”

Gustav peered up at the bluff above us, which was by this time little more than a dim outline against the darkening sky.

“That’s a good question, Brother. I reckon we’ll find the answer a mile or so to the southeast.”

I thought of the curlicue of smoke we’d seen drifting up over the hills. “You think Uly’s got more men down here?”

Old Red nodded. “Only one way to find out. Let’s go.”

“So let me ask you. . .,” I threw out before my brother could give Sugar his heels.

“Yeah?”

“Do you want me to salute when you give an order, or will a simple ‘Yes, sir’ suffice?”

“Try the salute,” Gustav sighed. “The less talkin’ you do, the better.”

He quickly got his horse up to a pace that seemed a touch speedy for night riding, but the added risk must have been worth it to him, for it kept us from conversing for a good fifteen minutes. By the end of that time, a rank, musky odor was assaulting my nostrils. It was the smell of a thousand wet dogs rolling in manure.

“You catch a whiff of that?” Gustav asked as he brought Sugar to a stop.

“Hell, yes. That ain’t my nose in your pocket—though I almost wish it was if it’d spare me a snootful of this.”

“The herd must be nearby.”

“Yeah, but a herd of what—polecats?”

“Whatever they are, we don’t wanna rile ‘em up and get ourselves spotted. We’d best take the last stretch afoot.”

I saluted. Old Red ignored me.

We left the horses behind a thick tangle of huckleberry bushes in a shallow gully. We hadn’t taken a dozen steps before a strange, raspy squeal froze us in our tracks.

“Boar?”

“No,” Old Red answered, the word coming out slow and uneasy.

We took a few more steps before another bleating cry stopped us.

“Sheep?” I asked.

“No.”

We started off again—and again the sound of something braying or bawling close by glued our boots to the ground.

“Uhhh. . .goat?” I asked, though I knew better.

“No.”

“Well, you can’t tell me that’s no cow.”

Yet when we finally got out of the gully and saw a long stretch of grassland laid out before us, it did indeed appear that the caterwauling had come from cattle. Dotted here and there across the moonlit plain were the hulking silhouettes of maybe four hundred beeves bedded down for the night. They seemed to be brahmas, having dark hides and an uncommonly lumpy look about them. As we drew nearer, however, I could make out what appeared to be clumps of fuzz on the closer specimens, and they lacked the wrinkly, low-hanging wattle for which brahmas are known. Though we were still a good fifty feet from the nearest of them, the musky scent of the herd was clogging up my nose like rancid oatmeal.

“What the hell are these shaggy—?”

Gustav shot me a shush and pointed off to our right. Perhaps a quarter mile away a rectangle of flickering orange pierced the nighttime blackness—firelight in an open doorway. I gave it a long squint and managed to make out the boxy outline of a smallish cabin.

“Come on,” Old Red whispered.

We moved slowly along the outer ring of the herd, the animals’ choking squalls sending fingers of ice up my back. As we approached the shack, a different noise drifted out to greet us—the sound of conversation. Two rough male voices ran into and over each other, with a third, quieter voice joining in from time to time so soft I could barely make it out.

Before long we were close enough to pick out words and phrases, though what we heard was hardly helpful.

“When we mumble mumble mumble Miles City mumble mumble eggs and taters!”

“First mumble the Gaities mumble whiskey mumble mumble Squirrel-Tooth Annie! How ‘bout you, mumble?”

“Whisper mumble whisper mumble mumble whisper mumble.”

It sounded like typical bunkhouse bullshit—cowboys blowing wind about the restaurants, saloons, and whores they’d patronize upon their return to town. Yet Gustav kept creeping closer, no doubt hoping the talk would turn to something useful. Before it could, however, our eavesdropping was interrupted by a hulking black shape that loomed up before us.

Now most cattle, even your he-stuff, lean more toward meek than mean. Jittery they can be, but they’re rarely truly ornery unless they have a reason.

But this was plainly no ordinary critter. It hauled itself off its huge haunches and greeted us with a distinctly unfriendly grunt.

What a man doesn’t want to do in such a situation, much as he might feel the urge, is turn tail and run. An angry bull will take this as an invitation to a square dance under the fellow’s hat, and big as that steer may be, he’s fast enough to get there before the party’s over. So Old Red and I had no choice but to stand there and stare at the big beast.

He was horned and hooved and four-legged, but there the similarities to your average beef ended. His skull was broad and round and so large a man could practically stretch out and take a bath in it were it be upturned and filled with hot water. A hump rose up behind the head like a dark, distant mountain. And the whole of the creature was matted with thick fur, a long black beard of it dropping from under his chin almost to the ground.

In short, the thing appeared to be half-bull, half-bear—a combination that didn’t bode well for us.

“When he charges, we split up,” my brother whispered.

“You really think he’s gonna—?”

I had neither the opportunity nor the need to finish my question, for at that moment the beast lowered his horns and came at us. Gustav sprang right, I sprang left, and that freight train of flesh passed right between us, coming so close I could feel the creature’s hot breath on my back.

As bulls have a turn radius akin to that of a covered wagon—meaning they require a stretch of space the size of Arkansas just to turn around—I should’ve had a decent chance of escape once I’d dodged that first run. Unfortunately, in hurling myself away from one danger, I put myself in the proximity of a hundred more. My mad dash had progressed but four steps when I realized I was running into the herd.

A black mound of hair blocked my route, and I was moving so fast that getting around it wasn’t an option. So I took it with a jump, stretching my legs out and sailing above it like a jackrabbit hopping over a log. As beautiful a hurdle as it might have been, I had no time to revel in the glory of it, for I heard the pounding of hooves behind me, and another dark shape was huddled up ahead.

I leaped again, clearing this newest obstacle by a mole’s whisker. When my feet hit dirt, I saw that I had enough space before me to turn back out of the herd. Only one more critter stood between me and safety, and I approached it with the speed and confidence of a steeple-chase champion. I’m sure I would’ve cleared it, too, had the thing not stood up with a startled gurgle just as I made my jump. I smacked into its mangy hide like a snowball dashed against the side of a barn, coming

down hard on my saddle warmer with my legs splayed out in a wish-bone U. Naturally the frightened animal took to running, and one of its hind hooves stamped the ground so tight on the inseam of my trousers that I could hear my unborn children crying out in mortal terror.

I sat there in a daze until my brother’s frantic “Otto! Behind you!” snapped me out of it. I looked around just in time to see that bullish, bearish beast coming at me again, his stubby horns at the perfect height to catch me through the eyeballs. Being flat-ass on the ground, all I could do was roll—which I got to with gusto, not minding the patties I flattened so long as the creatures who’d made them didn’t flatten me.

Heavy hooves pounded the ground, missing me by a distance so slim you could bottle it in a thimble.

“Over here, Otto! Over here!”

I crawled toward Old Red as fast as my belly could take me. He’d managed to get himself into the gully from which we’d emerged minutes before, and he urged me to join him in his usual warm, fatherly fashion.

“Get up and run, you damned idjit!”

I hopped up and took to my heels, managing to cover the last few feet of ground before my innards decorated the grassland. Once I was safely hunkered down next to Old Red, I looked back at the chaos I’d left in my wake. Big black shapes were awhirl in the dim light, squealing and bellowing as they barreled this way and that. As eerie a sight as this was, it didn’t chill my blood half as cold as looking over toward the cabin, for framed in the doorway glow was the outline of a man. A straight line of shadow cut across his midriff, and even without catching any glint of steel I knew it was a rifle.

I turned to tell my brother, but before I could pop out a word he opened his mouth and produced a truly remarkable sound—a long, loud howl so convincing I had to wonder if the Amlingmeyer family had at some point diluted its pure German blood with a few drops of lobo. Gustav cut off his cry with a yip-yip-yeowow so sudden and piercing-high it sounded as if it came from a different animal entirely.

Though this little ruse might convince the fellows in the cabin it was a pack of wolves riling things up, not a couple of nosy brothers, I didn’t see how that would save us. Surely these were line-camp hands we were dealing with, and they’d grab their guns and lanterns and hustle out quick to protect the herd.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

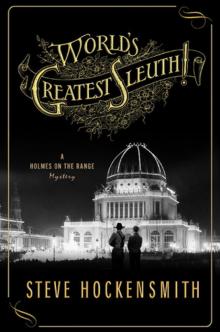

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!