- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

On the Wrong Track Page 22

On the Wrong Track Read online

Page 22

“You ain’t gonna help look for Chan?” he asked us.

“Not Wiltrout’s way.” Gustav got down on his knees and peeked beneath the nearest seat—which just happened to be Chan’s. “Hel-lo.”

“Now I know Doc Chan ain’t exactly tall,” I said, “but there is no way you just found him stuffed under his seat.”

“It ain’t Chan I’m lookin’ at.”

My brother stood up wearing that empty-eyed expression he gets on his face when his brain goes galloping off and leaves his body behind.

“Well, what did you see?” Kip asked.

“Nothing,” Old Red replied dreamily.

“For ‘nothing’ it sure made an impression,” I said.

Gustav nodded slowly. “Sometimes nothing tells you something when something would’ve told you nothing at all.”

Several of the passengers were staring at us now—including Miss Caveo, who’d swiveled around and put her book down.

“My brother, the philosopher,” I said to her.

She smiled. “He sounds like a nihilist.”

“If that means he’s talkin’ like a lunatic, I’d have to agree.”

The lady’s expression turned serious. “Did I hear you say you’re looking for—?”

Old Red stepped between us. “Sorry, miss—no time for chitchat.” He pointed at the front end of the car. “The widow,” he said to me. “She’s our best bet.”

I offered an apologetic shrug as my brother herded me away, but Miss Caveo didn’t seem inclined to accept just then. She wasn’t simply staring daggers at Gustav’s back—she was staring swords, bullets, and cannonballs.

“Must you be so damned rude?” I said to Old Red.

“Must you be so damned dense?” He waited a moment—till we were well past the lady—before saying more. “That nothing under Chan’s seat … it ain’t hard to Holmes out what it means.” He glanced back at Kip, who was tagging along behind us. “I bet you got it figured.”

“Well,” the news butch began, sounding uncertain, “I guess you should’ve seen his valise or carpetbag—whatever he’s usin’ to tote around his clothes and toiletries and all. Samuel would’ve stowed it down there when he folded up the Chinaman’s bed for the day.”

“So if Chan’s bag is gone … ?” my brother coaxed.

“Yeah, alright,” I said. “It took me a little time, but I got there. You’re thinkin’ Chan slipped off the Express last night.”

“Could be. And I figure I know how to find out for sure if he did. But first … pardon me, ma’am.”

Old Red brought us to a stop facing Mrs. Foreman and her matching set of curl-topped terrors. The widow was slumped against a window, her veil over her face. It was impossible to say if she was awake or asleep—or alive or dead.

Harlan and Marlin, on the other hand, couldn’t have been more lively. They were up on the seat across from their mother, bouncing so high off the cushions it was only a matter of time before one or the other flattened his head against the ceiling.

There was a rustling like the wind through a pile of dried-out leaves—the crepe and crinoline of Mrs. Foreman’s mourning dress crinkling as she pushed herself upright. She turned toward us, and I could make out the barest outline of an embarrassed smile lurking behind the dark gauze of her veil.

“I’m sorry. Are the boys bothering you?”

“Not at all, ma’am,” Gustav assured her with as much cordiality as he could muster—which wasn’t much. He placed a hand on the back of the boys’ seat (doing his best not to let on that he was leaning against it for support) and kept his gaze on the widow in a way that might have seemed piercing if you didn’t know he was trying to block out the craggy peaks and ravines whipping past the window behind her. “Actually, I need to talk with you in my official capacity.”

The twins stopped their hopping.

“How could I help you?” Mrs. Foreman asked, an extra quaver in her already timorous voice.

It’s funny the power a badge has over some folks. Pin a star to even as unimpressive a physical specimen as my brother, and they’ll break out in a sweat if he so much as tips his hat.

Of course, a badge has the opposite effect on certain other people—six-year-old boys, for instance.

“Did you ever find that snake?” either Harlan or Marlin asked.

“Or are you here to ask us about the robbery?” his brother threw in.

“We didn’t see much—Mother wouldn’t let us get out of our berth.”

“We could hear what happened to you, though.”

“The Give-’em-Hell Boys really gave you a whupping!”

“Harlan, Marlin—don’t be impolite,” Mrs. Foreman chided them weakly. “And remember what I said about that name.”

“Yes, Mother,” the boys sang in unison.

One of them turned to the other and cupped a hand against his brother’s ear.

“The Give-’em-Heck Boys,” he “whispered” loudly.

Kip chuckled, which was all the encouragement the twins needed. They doubled up laughing, then went back to jumping on the seat shouting, “Heck! Heck! Heck!”

“Boys,” Mrs. Foreman said in that hopeless tone mothers use when they know they’re going to be ignored.

“It’s not actually the robbery I need to ask about,” Old Red said to her. “It’s Dr. Chan—the Chinese gent.”

Harlan and Marlin settled down again, eager to listen in.

“What about him?” The widow sounded puzzled and discomfited, as if she couldn’t understand why such a disagreeable subject as a Chinaman would be brought up in the presence of a lady like herself.

“I happened to notice our conductor havin’ words with Dr. Chan last night,” my brother said. “Forceful words. Seein’ as your berths are so near Mr. Wiltrout’s, I was hopin’ you heard what it was that agitated him so.”

“Why don’t you just ask Mr. Wiltrout or Dr. Chan?” Mrs. Foreman asked—thus giving Gustav part of the answer he was looking for. If she hadn’t heard anything, she would’ve simply said so.

“We’re havin’ trouble findin’ Dr. Chan at the moment,” Old Red tried to explain. “And Mr. Wiltrout … well …”

There was no mannerly way to say he already had asked Wiltrout—and was now testing the truthfulness of the man’s reply. So I jumped in with a lie. In polite circles, I’ve found, it’s often the best way to go.

“We did ask him, ma’am. But he says he was so sleepylike, he don’t remember the conversation at all.” I shook my head gravely. “The poor man’s been under such a strain, you understand.”

“Well.” The widow considered her audience—two bruised, contused, rather scruffy-looking men and a gangly, overeager kid in a news agent’s uniform. Badges or no, we couldn’t have inspired much confidence, and Mrs. Foreman seemed reluctant to admit to eavesdropping just for our benefit.

Fortunately, her sons had no such scruples to overcome.

“We heard it!” one of them proclaimed, hopping higher than ever.

“We heard it all !” added the other, bounding into the air beside his brother.

“Boys—,” Mrs. Foreman began. But their little mouths were already racing too fast to be reined in.

“The China-man said he wanted to check on his luggage!”

“And the conductor said no!”

“So the China-man said, ‘I’ll give you twenty dollars if you let me into the baggage car!’”

“And the conductor said—”

The twins looked at each other, identical expressions of crazed glee on their cherubic faces as they matched each other bounce for bounce.

“‘You filthy little monkey!’” they shrieked.

“And then later—,” Harlan or Marlin went on.

“A lot later!”

“—after the snake tried to bite you—”

“Whoa! The snake!”

“—we heard the China-man come back!”

“And this time all he said was—”

; “‘Puh-leaze!’” they called out together.

They came crashing down on their butts side by side, snickering.

“That’s all you heard the second time?” Gustav asked. He’d been following the boys’ story so intently I almost expected him to start jumping up and down with them. “‘Please’?”

“That’s all he said.”

“But we heard someone moving around.”

“Like he was getting out of bed.”

“We peeked when we didn’t hear anymore.”

“But the China-man was already gone.”

Old Red drifted off into one of his stupors again, staring over the twins’ heads as the rest of us stared at him. Since no more questions—in fact, no words of any kind—seemed to be coming from my brother, I thanked his little spies for him.

“Nice job, you two,” I said, bending down to further tousle either Harlan or Marlin’s already mussed-up hair. “You’ve got yourselves some mighty fine ears under all them curls.”

Usually, Gustav sort of eases himself down from the clouds after he goes floating off. But for once he came crashing back to earth with a thud.

“Hel-lo! Yes! Good Lord!”

He turned on the widow with such quickness she cringed.

“Ma’am!” he said, stuffing a hand into one of his pockets. Then he seemed to trip over his own excitement, and he muttered, “Oh my,” looking embarrassed. He drew his hand out again and rubbed it absently over his chin.

“Yes?” Mrs. Foreman prompted him, though she didn’t seem eager to hear what he might say.

“Ma’am,” Old Red began again. “Please. I hope you’ll forgive my askin’, but … your husband. He was a young man when he passed?”

“My husband?” the widow gasped, the thin crepe of her veil fluttering slightly. Obviously, a question about her dearly departed was the last thing she’d expected. “Why, yes. He was only thirty.”

“He had a heart attack,” one of her sons reported solemnly.

“In Chicago,” the other added, equally somber.

“Boys,” Mrs. Foreman said, the word coming out harder than before—almost like a threat.

“At the Exposition.”

“On the Midway.”

“Boys,” the widow said again.

“In the Street in Cairo exhibit.”

“Watching girls dance the hootchy-kootchy.”

“Boys!”

Harlan and Marlin took to staring at their shoes, silent and still, for once.

“My condolences, ma’am,” Gustav coughed out. He couldn’t have looked more mortified if the widow had jumped up on her seat and had a go at the hootchy-kootchy herself. “I hope you won’t mind just one more question. Your sons … they take after their father? Looks-wise, I mean.”

“Yes.”

Mrs. Foreman seemed to be on the verge of saying more, but she held back, as if waiting for something. Too late, I realized what it was—a handkerchief from one of the “gentlemen” nearby. When none of us leapt to do the chivalrous thing, she reached into her handbag and produced a delicate hankie of her own. She maneuvered it under her veil and dabbed at her eyes even though no actual tears seemed to appear.

“I’ve seen pictures of Christopher—my husband—when he was a child.” She turned a bittersweet gaze on Harlan and Marlin. “The resemblance is remarkable.” When she looked back at Old Red again, her voice turned so cold any tears she might’ve shed would’ve turned to icicles on her pinched cheeks. “Why do you ask?”

“Oh, they’re just such fine-lookin’ lads,” Gustav said, making a half-assed stab at nonchalance that quickly collapsed into stammers. “N-not that you’re not fine-lookin’ yourself, I mean. For a widow. Y-you know. In a p-proper, ladylike, widowy sorta way.” He cut himself off with a mighty sigh. “Ma’am, as you’ve no doubt noticed, I am an utter simpleton—and a very tired one who’s feelin’ more than a bit poorly. So let me just apologize for intrudin’ and wish you and your sons a very pleasant journey back to San Jose.”

Mrs. Foreman acknowledged the apology with a slight tilt of her head, though she didn’t bother responding to (or contradicting) anything my brother had said.

Kip and I added our own good-byes, which were received with equal iciness by the widow but not her twins. Marlin and Harlan smiled and waved as we left, then leaned out into the aisle to watch us follow Old Red toward the front of the car. When I turned to wave a last farewell, I saw that someone else was watching, too: Miss Caveo was peering at us over the top of her book.

I waved to her, as well. And she waved back.

“What was that all about with the widow lady?” Kip asked as we gathered near the door to the forward vestibule.

“I can show you … if you’ll help us,” Gustav said. He sounded both grave and eager, like a man in a hurry to get to his own funeral. “But I gotta warn you—there might be some danger.”

“Danger?” Kip’s face flushed red behind his freckles. “Does this have anything to do with the Give-’em-Hell Boys … or Joe Pezullo’s murder?”

“It has everything to do with both.”

The news butch looked terror-stricken. “Jeez … in that case … if you think it might be dangerous”—he let a cocksure grin bust through his mask of fear—“you’d darned well better let me help. What do I gotta do?”

My brother gave the boy a slap on the back. “Just whip out your passkey, kid … and then be ready.”

“Ready for what?” I asked.

“Answers,” Old Red said, and he turned and headed for the baggage car.

Thirty-one

ANSWERS

Or, We Find Solutions to Our Mysteries, but Not Our Problems

Gustav led us into the baggage car, his hand hovering over his holstered .45. When we were all inside, he skulked off to scout things out—and ordered me and Kip to “fort up” the door.

“You want us to what now?” I said.

“Fix it so no one can get in here ’less we want ’em to,” Old Red called back, disappearing into the stacks of baggage. “Push Pezullo’s desk in front of the door, maybe. Or gum up the handle somehow. Whatever you can do. We don’t want anyone bargin’ in here till we’ve seen what we’ve come to see.”

“Which is?” Kip asked as he strolled over to the car’s only chair (its mate having been buried in the Nevada desert tethered to a dead hobo). He dragged the chair to the door and jammed it under the handle.

When Gustav reappeared, he gave the makeshift barricade his approval with a single downward jerk of his head. Then he picked Pezullo’s crowbar up off the desk, walked across the compartment, and dropped it atop the plain pinewood casket Chan was hauling back to San Francisco.

“Aww, jeez!” Kip moaned, looking horrified. “You can’t be serious!”

I stepped up to the coffin and knelt down beside it. “No need to fret, kid. There ain’t no body in here.” I looked over my shoulder at Old Red. “Right?”

My brother’s response did little to bolster my confidence: He shrugged, then backed off a couple paces to give me room to work—or to get out of smelling range should Lockhart’s tale of a casket packed with “treasure” prove untrue. There was a crunch underfoot as he moved, and he crouched down to peer at whatever he’d just ground into the floorboards.

“Sliver of glass.” He looked up and scanned the car. “Either of you see that empty whiskey bottle that was in here yesterday?”

Kip and I shook our heads.

“Must’ve broke,” Kip said, still looking rattled by our would-be grave-robbing. “We’ve sure had enough sudden stops to do it.”

“I suppose. But then the question is, who swept it up?” Gustav stood slowly, wobbling with the car’s gentle swaying as he strained to straighten his legs. “Anyway, we got us other questions to attend to first.”

“Shall I begin attendin’ then?” I asked.

Old Red nodded, and I dug in the crowbar’s claw.

“Wait!” Kip yelped. He appeared to have lost his

appetite for adventure—and looked like he was about to lose his breakfast, as well. “This ain’t a good idea, fellers. It’s a miracle Wiltrout ain’t got you fired already. Bust open a coffin on his train, and he’ll see to it you never ride the S.P. again, let alone work for it.”

“I could live with that.” I turned to my brother. “You?”

“Yup.” Old Red gave me another nod.

I worked cautiously at first, prying the lid up just a fraction of an inch. When no cloud of rot gas came billowing out, I grew bolder, tugging one side of the lid up high enough to get a peek inside.

“It’s stuffed with straw,” I was relieved to report. Both Kip and Gustav suddenly found the nerve to crowd in closer.

With a few more quick jerks, I got the lid off entirely. I prepared to shield my eyes lest I be blinded by the sparkling of rubies, sapphires, and carbuncles. But black velvet doesn’t put up any kind of gleam whatsoever, and that’s what we saw packed in the straw.

There were maybe a dozen wads of velvet visible, with plenty of room for more to be buried beneath them. They ranged in size from apple-ish to pumpkin-ish, with most leaning to the smaller side.

I picked up one of the little bundles and gingerly unwrapped it, Kip and Old Red pressing in on either side to watch. Beneath the velvet was newspaper, and beneath that cotton.

What I found under that last layer did indeed glisten, in a cold, hard, flat kind of way. But it was no precious gem.

It was porcelain—and it was very familiar.

I was holding a small, handleless cup exactly like the one Old Red had found in the desert after the robbery. As if there could be any doubt, my brother produced the cup’s twin, and we held them up side by side.

They were as much a match as Harlan and Marlin. The size, the dark blue pattern running around the rim, the leaves painted on the side—everything was identical.

While I rewrapped the cup I’d taken out, Old Red gently settled his back in the straw like an egg he was returning to its nest. Then he fished out the biggest bundle in the box and unswaddled it just enough to give us a glimpse of a large, ornate teapot.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

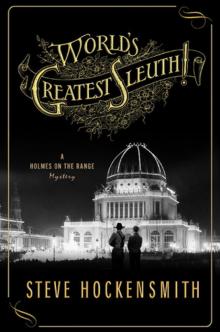

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!