- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

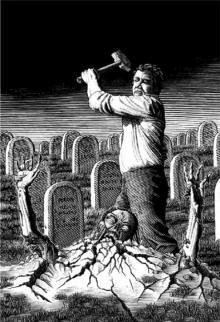

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Page 23

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Read online

Page 23

“I hear you lost your guard.”

“Yeeeeesss,” the doctor drawled, still tapping away, eyes squinting up at nothing. “Pity, that. Good thing I didn’t step out for a midnight snack or I’d have been one.” He clapped his hands together and focused on Elizabeth again. “But that’s neither here nor there. I was about to tell you about Mr. Smith’s re-Anglification.”

“His what?”

“Re-Anglification! That’s what I call my process. Or plan to call it. If it works.”

Dr. Keckilpenny darted over to a dark corner of the room. On the floor was a jumble of assorted bric-a-brac, and the doctor knelt down next to it.

“Mr. Smith isn’t just a dead man, Miss Bennet. He’s a dead Englishman. And if—as we’ve discussed before—some part of his mind still survives, then this is how it might be reached, and even revived.”

Dr. Keckilpenny began grabbing dishes and holding them up to display their contents.

“Trifle. Currant scones. Cup of tea. Good! Mangled viscera? Bad.” He pointed at a small stack of books. “Shakespeare. Milton. Dr. Johnson. Good!” He reached out for a plate covered with a stained napkin, then changed his mind and simply pointed at it. “Body parts? Bad … when they’re not attached.” He swung his finger to a pile of framed portraits. “The king. The prime minister. The Prince Regent. Good! Sort of.” He gestured at a sealed jar in which a loaflike mass floated in brackish brine. “Brains? Bad bad bad.”

“Grrrrrrrrrrrr,” Mr. Smith said.

“Grrrrrrrrrrrr, bad,” Dr. Keckilpenny replied. “Words, good!”

“Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr.”

“I hope you’ll forgive the observation,” Elizabeth said. “But Mr. Smith doesn’t strike me as any more English than when we captured him.”

The doctor nodded sadly. “Yes, I know. He’s definitely responding to something, though. The last hour, he’s seemed more alert. Aware. Almost perky.”

Elizabeth looked at the hollow-eyed thing leaning toward her groaning. “Perky?”

The doctor nodded again, this time with excitement. “I think it might be the music. It hath charms to soothe a savage breast, you know, and you won’t find many breasts more savage than a zombie’s. That’s what got me thinking about you, Miss Bennet. If the sound of a waltz could stir something in Mr. Smith, just think what the sight of one might do.”

“I don’t understand. What has that got to do with—”

Dr. Keckilpenny started walking toward Elizabeth. She knew what he was going to say before he said it.

What she didn’t know was how she would reply.

The doctor offered her his hand. “Miss Bennet, may I have this dance?”

Elizabeth said nothing, but she did take his hand and stand.

Dr. Keckilpenny walked her out to the center of the room, then slipped his right hand around her waist while lifting her left hand up high.

“A waltz,” he said, his voice as soft as she’d ever heard it. “How like the count to choose something so risqué for a country dance.”

“The baron,” Elizabeth corrected as the two of them began to move in time to the muted music of the ball. There was a little warble to her voice that surprised her.

She should have been out dreadful-stalking with Master Hawksworth. That’s where she’d intended to be. So why was she letting Dr. Keckilpenny spin her in sweeping circles around an attic?

“Grrrrruh!” Mr. Smith barked. “Grrrrrrruh!”

“That’s progress, perhaps,” the doctor said. “What are you trying to tell us, Smithy? Are you asking for the next dance?” He looked down into Elizabeth’s eyes in a way that made her dizzy. Or maybe that was just the waltz. “Well, you can’t have it.”

Mr. Smith’s gruff, yapping growls grew louder, and he began to struggle, stamping his feet and straining harder against his chains.

“GRRRRRUH!” MR. SMITH BARKED. “GRRRRRRRUH!”

“I do believe he’s jealous,” Elizabeth said. “The way you’re holding me, he probably thinks you intend to devour me.”

“Not a bad theory, Miss Bennet. Shall we put it to the test?”

And he pulled her tightly to his chest and leaned in and kissed her.

Instantly, entirely by instinct, Elizabeth broke his hold with the Wings of the Phoenix, an upward sweep of the arms that sent him flying back into the nearest wall.

The doctor let out an “Oof,” then stumbled forward, off balance. When he regained his footing he gaped at Elizabeth, looking as much puzzled as hurt.

“Have I offended you? It was purely in the interest of scientific inquiry.” He cocked his head and furrowed his brow. “I think.”

“Doctor, I … I don’t know what to say.”

But someone did.

“Buh ruh,” Mr. Smith said. “Buh ruh!”

Dr. Keckilpenny burst out laughing. “Did you hear that? We did it! We did it, Miss Bennet! He said … something!”

He took a step toward Elizabeth as if he intended to hug her or take her hands in his, but then he suddenly stopped and spun toward Mr. Smith again.

“Oh. Right. Sorry. Well well well.”

“Buh ruuuuuh!” Mr. Smith brayed. “Buuuuuuh ruuuuh!”

His struggles grew more frantic even as his words—whatever they were—grew louder.

“It’s just like last night, when he went into his frenzy,” Dr. Keckilpenny said. “Only with the ‘buh ruh,’ now. I wonder if—”

“Doctor, listen. The music.”

“What of it? I don’t even hear … oh.”

The music had stopped.

Elizabeth whirled around and shot down the stairs. When she got through the door at the bottom, she found the sentry gone.

From down the hall, toward the master staircase and the foyer beneath, she could hear a great commotion: murmuring, shouting, the shuffling of many feet.

Elizabeth unsheathed her katana and sprinted toward the sound.

“What is the meaning of this?” she heard Lord Lumpley roar.

“Isn’t it obvious?” a familiar (and very welcome) voice replied just as she reached the top of the main stairs. “We’re crashing your party, My Lord.”

Down below, Elizabeth could see her father and Master Hawksworth squared off against the baron and Jane as a teeming stream of people flowed around them into the house.

There was Mr. Maleeny, the blacksmith, with his family; Mr. and Mrs. Littlefield, who ran the local bakery; Mr. Lawes, the carpenter, with his sons Humphrey and Giles; the McGregors, who sold lamp oil and perfume; the Calders and the Masons and the Crowells and many more. All of them tradesmen or tradesmen’s kin. And they weren’t even coming in the servants’ entrance.

“Blast you, Bennet!” Lord Lumpley railed. “You can’t do this!”

“I think that you’ll find, very soon, that it’s done,” Mr. Bennet said. “And just in time, too. We aren’t the only uninvited guests who’ll be calling on Netherfield tonight, I’m afraid.”

“So they’re here?” Capt. Cannon called out. What with the throng clogging the entrance hall, his Limbs couldn’t maneuver him any closer than a doorway on the other side of the room.

“Yes,” Mr. Bennet said to him, and Elizabeth heard a sudden, barely suppressed fury in his voice. “The hordes are descending at last, Captain. Not five minutes behind us are dreadfuls beyond number.”

“What should we do?” Elizabeth asked.

Mr. Bennet looked up at her and, seeing the katana in her hands, smiled.

Master Hawksworth looked up at her and, seeing Dr. Keckilpenny step up close behind her, frowned.

“Oh, tonight’s the easy part,” Mr. Bennet said. “All we must do is survive.”

__________________

CHAPTER 33

OSCAR BENNET’S OLD DREAM, the one about his daughters fighting beside him in the honorable warrior way, was about to come true at last. He knew that when the moment arrived, however, only part of him would be able to appreciate it. The other part—the vast majorit

y of him, in fact—would be too busy trying to keep his entrails inside his own stomach. So he paused to savor the moment now.

They were all lined up with him before the manor house: Mary, Kitty, and Lydia, who’d left Longbourn to track him down as he’d swept through the countryside forging his little diaspora; Jane, there over the objections of Lord Lumpley (who didn’t wish to be parted from his bodyguard) and Lt. Tindall (who insisted that his troops could do what needed to be done without endangering “those whose dainty hands should never have been soiled by instruments of war”); and finally Elizabeth, standing at the end of the line with Geoffrey Hawksworth quite literally looming up behind her, just as he’d loomed a little too large all through her training.

Mr. Bennet had his doubts about them all. Yet when he’d announced that the Bennets would be the last line of defense, guarding the front door while Capt. Cannon’s soldiers nailed wooden slats over the windows, his daughters’ only hesitation before following him outside was to collect their favorite weapons.

Long ago, he’d broken his vow to the Order to raise his children in the warrior way. They seemed poised to redeem his honor now, though. He could die a happy man. And very soon, he might.

It started with the occasional blast and flash of gunfire out by the road, where Lt. Tindall had stretched out his own thin skirmish line. The screaming followed, some human, some not, and not long after came the lieutenant’s far-off cries: “Stand your ground!” and “Hold fast!” and finally “Hold, damn you! Hold!” Then the soldiers started streaming back across the long, moonlit lawn. One by one and two by two they came, all of them sprinting wild-eyed toward the Bennets and the house.

“LieutenantTindall,” Jane said, taking a hesitant step toward the road.

Elizabeth stepped with her. “Perhaps we should—”

“No,” Mr. Bennet said. “The Enemy will come to us in its own good time. There is no reason to rush, and every reason not to.” He looked back over his shoulder at the little figure pacing nervously before a group of frantically hammering soldiers. “How much longer?”

“A few minutes,” Ensign Pratt squeaked. “If only this bloody house didn’t have so many bloody windows!”

“Language,” Mr. Bennet chided.

“Sorry, Sir. My apologies to the ladies.”

Lydia leaned in close to Kitty and whispered something, and they both giggled. Mr. Bennet found it comforting, somehow. The two of them would still be gossiping and laughing as they crossed the River Styx.

The first of the fleeing soldiers rushed past and darted through the front door.

“They have sent boys to do the work of warriors,” Master Hawksworth grumbled.

“Yes. It has been known to happen,” Mr. Bennet said. He pointed at a far corner of the lawn. “Ahhh, the guests of honor arrive at last.”

One of the men running toward them had a peculiar, herky-jerky quality to his stride, and his head was bent so far to the side it appeared to be resting horizontally atop his right shoulder. As he came nearer, it became clear he wasn’t dressed as a soldier. He was chasing one.

Mr. Bennet brought up his crossbow, took a moment to squint down the stock, and squeezed the trigger. The bolt shot across the lawn and buried itself in the dreadful’s forehead with an audible thunk.

“It appears the first kill of the night goes to me,” Mr. Bennet said as the unmentionable tumbled to the ground. “Sorry to be selfish.”

Within moments, there were zombies enough for all. Some ran from the shadows, some staggered, some crawled. Some were men, some women, some children. Some wore ragged shrouds, some bloody clothing, some absolutely nothing. Yet they all had one thing in common: They were headed toward the house.

“Remember your training, and we shall triumph!” Master Hawksworth bellowed, waving his sword above his head. “Battle cries, warriors! Battle cries!”

The girls brought up their katanas and screamed in unison.

“HAA-IEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

“Yes, yes,” Mr. Bennet said. “Haiee.”

He’d never put much stock in battle cries, actually, but they did seem to help the beginners. And his daughters, inexperienced as they were, showed no sign they might turn and flee inside as the soldiers had. They looked frightened, of course, with pinched, pale faces and wide eyes. Yet their feet were planted firmly in battle-ready stances, and their weapons didn’t waver.

Mr. Bennet nodded his approval, then turned back to the wave of death sweeping toward them. The swiftest dreadfuls were but a dozen strides away now, and he brought one down with another bolt before handing his bow to a soldier as he flew past blubbering hysterically.

“Put this in the house for me, there’s a good lad.”

He drew his sword just in time to slice the head off a zombie wearing the black robe and mortarboard of a university don.

“The Hawk and the Dove, Master?” he heard Elizabeth say, and he spared a glance her way, curious to see how Hawksworth reacted.

The Master was doubled up with his hands wrapped around his right leg.

“Ahhhh! My knee! Again! Blast!”

It had been the same earlier that day, when they’d spotted their first small herd of unmentionables. Hawksworth’s “old sparring injury” had hobbled him, for a time.

“Master!” Mary cried, and she put a bullet through a dreadful’s head and cleaved another’s in two to reach the young man’s side. “Do you need help?”

Hawksworth swiveled, grimacing, and began limping toward the door. “I will be fine. But, alas, I’m useless to you now! Try to carry on without me!”

“Go, all of you!” someone shouted. “For God’s sake, get inside!”

Mr. Bennet turned back toward the lawn. Lt. Tindall was weaving wildly up the gravel drive, all of his attention on Jane even as one unmentionable after another swiped and lunged at him.

Mr. Bennet started toward him, but a brief encounter with another mindless, slobbering don proved to be a distraction. By the time a second mortarboarded head was at his feet, Jane and Elizabeth were already on either side of Lt. Tindall, rushing with him toward the house along a newly made lane of crania, arms, and torsos.

Mr. Bennet’s chest went tight with pride even as he beheaded a groaning old woman with her intestines hanging out through a hole in her nightgown.

“Finished in the back!” he heard Capt. Cannon call out.

“Finished in the front!” Ensign Pratt yelped.

“Capital,” Mr. Bennet said. “Girls, I do believe a retreat is in order.”

Unmentionables kept coming at them as they backed toward the door, with more continuing to step out of the woods. There were too many to count—at least while chopping away at a new neck every few seconds—but Mr. Bennet thought he spotted at least half a dozen clad in red jackets and white cross belts.

The second he and the girls were inside, soldiers slammed the door shut and began nailing up boards to hold it in place.

Lydia and Kitty sheathed their swords and fell into each other’s arms, laughing. It wasn’t their usual giddy, frivolous tittering, though. They were laughs of disbelief and relief to find themselves still alive.

A hand settled lightly on Mr. Bennet’s forearm.

“Papa?” Jane said. “How did we do?”

Mr. Bennet glanced at Master Hawksworth, who was sitting, legs spread out, back propped against a wall. Both Elizabeth and Mary were leaning in over him.

“You were splendid,” Mr. Bennet said to Jane. “But there are tests yet for you to face.”

“What?” Capt. Cannon said. “Limbs! Pace!”

Right Limb and Left Limb began wheeling him around the foyer so he could scowl at panting, shame-faced soldiers.

“I’d say your daughters have already proved themselves more warrior than many another here.”

“If I’d had more men, it would have looked different,” Lt. Tindall protested. “So many were held back in the house.”

“One doesn’t fight dreadfuls in the da

rk, Lieutenant,” Capt. Cannon snapped. “When we face them again on the battlefield, it will be on our terms. Now, let us see to the—”

“I would have words with you, Cannon,” Mr. Bennet said. “Alone.”

“Limbs. Halt.”

The two men looked into each other’s eyes a moment. Mr. Bennet’s were full of rage; the captain’s, remorse.

“Limbs, to my chambers. Lieutenant, see to it there’s a man—or a lady—at every window and door. It’s going to be a long night.”

The pounding began before he’d even finished. One fist thumped against the door, then another smashed into a window, then another started in, and another and another and another until the whole house rattled and seemed to shudder. Some of the villagers packed into the rooms nearby screamed in terror, and their cries were answered by screeches from just outside.

“We must have calm!” Capt. Cannon roared. “The next person I hear shrieking will be put outside with the other banshees!”

The screaming stopped, for a time. As the captain and Mr. Bennet moved off into the north wing, they approached the room where Dr. Thorne, the company’s gruff old duffer of a surgeon, was seeing to the wounded.

“You’re lucky, boy. That’s not a bad scratch at all,” the doctor was saying as they passed by. “You’ll only lose the arm up to the elbow.”

Mr. Cummings could be heard offering comfort by reading haltingly from his Book of Common Prayer. It seemed to be a selection from the table of contents, however, and it was soon drowned out by the sound of sawing and all the attendant lamentations.

When they reached the bedroom Capt. Cannon had commandeered for his headquarters, the soldiers guarding the windows were dismissed and Left Limb and Right Limb positioned in their place. The captain was left in the middle of the room in his cart. Mr. Bennet, although offered a seat, chose to stand directly before him.

“Are you sure you want your men to hear this?” Mr. Bennet said, nodding at the Limbs.

“By necessity, I have no secrets from them.”

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

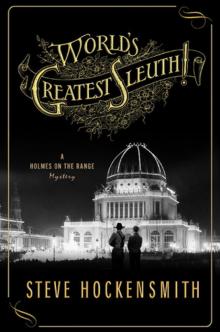

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!