- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

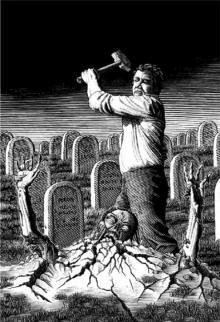

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Page 3

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Read online

Page 3

Elizabeth caught Jane’s eye and nodded quickly at the floor. Jane was the eldest of the Bennet sisters, the leader. It was upon her to set the proper example.

But what was proper? Elizabeth could see her sister wasn’t sure.

She gave her head another downward jerk, and slowly, reluctantly Jane sank to the ground, her black skirt swirling in gray dust. Elizabeth followed suit, then Mary, then Kitty. Lydia remained upright, defiant, until Kitty yanked her to her knees with a sharp tug on the wrist.

“Good,” Mr. Bennet said. “But not good enough. In future, whenever we are within these walls, I will expect instant obedience. If I do not get it, there will be grave consequences.”

“Oh, really, Papa!” Lydia scoffed. “I can’t picture you whipping us with a cat-o’-nine-tails like ‘Old Liu’!”

Mr. Bennet glared at her. “Then you must change your picture of me. Whilst we are training, I am not your ‘Papa.’ I am your master, and you will mind me accordingly.”

“‘Training’?” Elizabeth said. “What sort of training?”

“Before I explain, we must have the first lesson. To attend me carefully, without the distraction of unnecessary comfort, you will learn to sit as warriors do.” Mr. Bennet held out his hands, palms up, over his crossed legs. “Like me.”

“Sit as what do?” Lydia said.

“We can’t sit like that,” Kitty protested.

Mr. Bennet shook his head in disgust. “You’re all so quick to point out what you can’t do. The time has come to learn what you can.”

“Well, it’s certainly not very ladylike,” Lydia pointed out.

“Ladylike be damned!” her father thundered, and all his daughters gasped. Yet they all did as he said, too.

Or they tried to, at any rate. Layer upon layer of binding feminine underthings—shifts under corsets under petticoats—made even so simple a task as sitting on folded legs a challenge worthy of a Hindu contortionist. After ten minutes of not entirely successful sitting practice, Mr. Bennet declared that the girls were close enough, and he would begin.

“Years ago,” he said, “when the threat from the dreadfuls was at its worst, certain Englishmen—and Englishwomen—turned to the East for guidance.”

“You mean like Lady Catherine de Bourgh,” Mary said.

“Hush, child! I’ve only just started!”

Mr. Bennet took a moment to compose himself, and began again.

“Years ago,” he said, “when the threat from the dreadfuls was at its worst, certain Englishmen and Englishwomen—such as the famous Lady Catherine de Bourgh—turned to the East for guidance. In the Orient could be found specialized methods of individual combat that seemed perfectly suited to the problem at hand. This rankled our more fervent patriots, who would have preferred an English solution to an English problem. But those of a more pragmatic turn of mind—and the resources to follow its dictates—undertook the long trek to furthest Asia and apprenticed themselves to masters of the deadly arts. I was one such person.”

Jane, Mary, Kitty, Lydia—all could contain themselves no longer.

“You have been to the Far East?”

“You fought in The Troubles?”

“Did you meet Lady Catherine?”

And, from Lydia: “My feet fell asleep. May I move my legs?”

Only Elizabeth remained silent, patiently waiting for more. Her father’s words were a revelation, yet not entirely a surprise. It was more like the final piece in a puzzle: Even if it’s missing, one can know its shape from the blank space it’s meant to fill.

Elizabeth and her sisters had been living in that empty spot. It was their world.

Mr. Bennet held up his hands for silence. “Of my training in China, you will learn much. Of my experiences in The Troubles … you will learn what you must. And, yes, Lydia. You may move your legs.”

With much grunting and panting and little half-muffled exclamations of annoyance, Lydia began uncrossing her legs, a process that took—what with all the snags on her stay and halfslip and crumpled muslin—not less than a minute.

“Tomorrow,” Mr. Bennet said, eyelids wearily adroop, “you will wear simple sparring gowns. For now, however, it is the end of my tale that concerns us. After the Battle of Kent, when the dreadfuls were—supposedly—vanquished at last, I and my fellow initiates were expected to give up our warrior ways. Not to do so was to be seen as not entirely English anymore. Not entirely respectable. The pressure to acquiesce was quite intense, as you can imagine.”

He paused for a quick eyeroll toward the house.

Yes, indeed. Elizabeth could easily imagine.

“I built this dojo—this temple of the deadly arts—not just for myself,” Mr. Bennet continued. “I built it for you. My children. So that you, too, would be schooled in the Shaolin way. Now, far too belatedly, we begin your training. It will not be easy. You will be sorely tested. You will cry and bleed. You will face the derision, probably even the condemnation, of your community. Yet you will persevere on behalf of the very souls who now find you so ridiculous. For the dreadful scourge has returned, and once more warriors must walk the green fields of England!”

There was a long silence while the girls took all this in.

Eventually, Kitty cleared her throat.

“Ummm … what if we don’t want to be warriors?”

“Then I will disown you, and you will, most likely, be torn apart and eaten by a pack of festering corpses.” Mr. Bennet moved his gaze around the room, looking at each of the other girls in turn. “Any more questions?”

Elizabeth had several, of course. Yet, for some reason, one in particular came to her lips first.

“When do we begin?”

Mr. Bennet’s expression remained grim even as his eyes seemed to flash her a secret smile.

“It has begun.”

__________________

CHAPTER 5

FIRST, THE GIRLS had learned to sit. Next, they learned to stand.

The Natural Stance they mastered quickly, since it involved little more than keeping their feet together and their backs straight—exactly as they’d been taught by their mother and governesses all their lives. The Spread Eagle Stance took more getting used to. In fact, the first time their father said the words, “Now spread your legs wide like this,” Mary gasped “Really, Papa!” and Kitty declared that she couldn’t do it because it felt “naughty.”

From standing, they moved on to yelling.

“A battle cry,” Mr. Bennet said, “is a warrior’s calling card. Only it does not say, ‘Good afternoon. I have come for tea and crumpets.’ It says, ‘Death has come for you! Flee or be killed where you stand!’ And it does so like this.”

Mr. Bennet assumed the Spread Eagle Stance, scowled, and bellowed, “HAA-IEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

It was a very good battle cry indeed. So much so that Kitty instantly burst into tears. Once her father had her calmed, he asked Jane to try a cry of her own.

“Haiee,” she said.

“Did you hear that, girls?” Mr. Bennet cupped a hand to his right ear. “I do believe a mouse just coughed.”

Jane tried again.

“Haiee!”

“A consumptive mouse,” Mr. Bennet said.

“Haa-ieeeee!”

“Which has stubbed its toe.”

Mr. Bennet held up a hand and shook his head before Jane could unleash another of her half-hearted squeals.

“Your battle cry does more than announce your presence,” he said. “It prepares you for combat by shattering the shackles of good manners and gentility. It is not a sound a gentleman or lady would choose to make. It is an animal sound—the roar of a killer stalking the jungle. As Master Liu used to say, a good battle cry ‘unchains the tiger within.’”

“Perhaps I don’t have a tiger inside me,” Jane said.

“Everyone does, daughter. Everyone.” Mr. Bennet turned to Lizzy. “You try it.”

Elizabeth spread her legs, turned her feet outward, bent her k

nees, took a deep breath, closed her eyes—and split the world in two.

“HAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA-IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

When she opened her eyes again, Elizabeth found her four sisters gawping at her, slack jawed.

“She certainly has a tiger,” Lydia muttered, “and it’s rabid.”

“No,” Mr. Bennet said. “It is hungry.” He turned and headed for the door. “I must send word of what we saw in the church. Hopefully, we will not have to face what approaches alone. Keep practicing until I return, all of you.”

“You want us to just stand around yelling?” Lydia asked.

“Only until you get it right,” her father said, and then he was gone, striding across the lawn toward the back of the house.

“Haaiieee!” said Jane.

“Hiiyaaaa!” said Mary.

“Hooyaaah!” said Kitty.

“La!” said Lydia. “You have no idea how silly you all look!”

“Unfortunately, I think I do,” Jane sighed. “Yet we must trust our father’s wisdom.”

“What if our father’s a loony?” Kitty asked.

“You didn’t see him with Mr. Ford,” Elizabeth said. “What he did. It was not the work of a ‘loony.’ He is a warrior.”

“And so are we to be,” Jane said. Yet her words lacked the whip crack of conviction, and to Elizabeth she sounded resigned, not resolute.

“Outcasts, that’s what all this will make us!” Kitty said, putting on a prodigious pout she’d learned from her mother. “Social papayas.”

“Pariahs,” Mary corrected. “And there’s nothing wrong with standing apart. Fruitful, truthful observation requires a certain distance, I find, and our neighbors are entirely too—”

“Well, I don’t think it’s fair,” Lydia cut in with a petulant stamp of one of her not-insubstantial feet. (Though only eleven, she was by far the stoutest of the Bennet girls.) “Jane’s already out, and Lizzy will be within a fortnight, provided the Goswicks don’t cancel the spring dance. But what of Lydia and Mary and me? No one’s going to throw a ball for girls who run around screaming ‘Haaiiieee!’ like a bunch of savages.”

“Lydia,” Elizabeth said, shaking her head, “your coming out is still years off. You’d worry about a ball that far in the future when you saw an unmentionable in your church this very morning?”

Lydia shrugged. “Mr. Ford didn’t look like much of a threat to me.”

“Then imagine a thousand of him … with legs,” Mary said. “From what I’ve read, there were more than that many at the Battle of Kent.”

“So?” Kitty threw in. “That was Kent, and the battle put an end to them. Why, no one’s even seen one of the things in years.”

“Until today,” Mary said. “For all we know, there are a hundred of them out in the woods this very moment, and they ate Emily Ward just like Mamma said.”

Only Elizabeth noticed Jane wince.

“Well, Mamma also says there were never more than a dozen dreadfuls in Hertfordshire, even during the worst of it,” Kitty sniffed. “So there.”

“Mamma is not always right,” Jane pointed out, understatement incarnate.

“All the same,” Lydia said, “I’d still rather be an unmentionable than a spinster. If Father has his way, we’ll all end up like Miss Chiselwood.”

“Would that really be so bad?” Mary asked. “I’d hardly call becoming a governess a fate worse than death.”

Lydia put her fists to her hips. “I would! If I’m not married by the time I’m seventeen, I’m running away to Dover and throwing myself into the sea.”

As they had so many times over the years, Jane and Elizabeth shared a knowing glance and a mutual rolling of the eyes. It was actually a relief to set aside dreadfuls and battle cries and their father’s possible insanity and commiserate again, for just a moment, over something as harmless as Kitty and Lydia’s amour-mad ways.

“You may keep your date with the Channel when the time comes, if you so chose,” Elizabeth told Lydia. “For now, however, we must follow the path our father has chosen for us … no matter how outlandish it might seem.”

“Elizabeth is right. This is hardly the time to think of romance and matrimony,” Mary said. “We must set aside such frivolousness.”

“La!” Lydia snorted. “It set you aside a long time ago!”

“It’s easy enough to say we should forget about love,” Kitty added. “But I’d like to see any of you stick to it if some Sir Comely were to come along and woo you. Why, real passion can no more be ‘set aside’ than a dreadful will stay buried!”

Jane sighed.

“Sir Comely?” Elizabeth laughed.

“Mamma lets you read far too many novels,” Mary said.

Yet their young sister had said something wise, quite without knowing it. Which was the only way she was likely to do it.

“Please, everyone,” Jane said. “Let us return to our studies.”

“Hiiyaaaa!”

“Haaiieee!”

“Hooyaaah!”

“La!”

“HAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA-IIIIIIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

__________________

CHAPTER 6

THE SECOND DAY OF TRAINING began before dawn, with Mr. Bennet rousing everyone in the house by roaring “Novitiates, assemble!” over and over until everyone had hopped (or fallen) out of bed. The girls scrambled into their new sparring gowns and marched out to the dojo while their mother wailed about cracked windows and shattered nerves.

After warming up his pupils with some standing and yelling practice, Mr. Bennet moved on to actual hitting and kicking, although the girls had yet to hit or kick anything more solid than air. Then came the weapons. And the accidents.

Mary bloodied her nose with a quarterstaff. Kitty blackened her own eye with a pair of nunchucks and was inconsolable for a quarter hour. Lydia rebloodied Mary’s nose with a wooden practice sword.

Only Elizabeth and Jane managed not to injure themselves (or Mary), yet their father was obviously unhappy with their limp grips and hesitant movements.

“A warrior thrusts with the sword,” he barked at Jane. “You hold it out as if offering a guest a scone!”

“But I’m afraid I’ll hurt someone.”

“You want to hurt someone, child! Hurting someone is the whole point!”

Jane looked dubious.

Her father looked very, very troubled.

When the time for scones actually arrived, Mr. Bennet had no appetite for them or anything else on the breakfast table. Indeed, it was hard to see how anyone could eat with Mrs. Bennet fussing and flitting about as she was, clucking over this daughter’s bruise or that daughter’s scrape while continually haranguing her husband about his barbaric ways.

“I no longer need worry that our children will end up starving in the poorhouse. Obviously, their own father will see to it they’re beaten to death long before that could happen!”

Mr. Bennet toyed disconsolately with his toast, saying nothing.

“Just look at them! Two days ago, they were proper young ladies. Now they look like escaped bedlamites!”

“Mamma, please,” Elizabeth said.

Mr. Bennet sighed and stirred his tea, though his teacup was empty.

“You would throw away our respectability, our station, our prospects, because of a single unmentionable? I thank Heaven, then, that we only saw one. Two, and you’d have no doubt hurried home and burned Longbourn to the ground without waiting for ruin to overtake us!”

Mr. Bennet hid himself behind a letter the footman had just brought in.

“We may as well go lie down in the nearest cemetery and simply await our fate,” Mrs. Bennet went on. “With the estate entailed and no male heir, there is no hope for us. Oh, if only you were a boy, Mary, as you were once so often thought. But, alas, you are all quite irreversibly—”

“Lord Lumpley is coming.”

Mrs. Bennet whipped around to face her husband.

“The baron?” she asked.

“The baron.”

“Is coming to Longbourn?”

“Is coming to Longbourn.”

“To pay a call?”

“To pay a call.”

“On us?”

“On me. I sent a letter yesterday requesting an audience to discuss the incident with Mr. Ford, and Lord Lumpley has agreed, though he chose to pay a call here instead of summoning me to him.”

“I wonder why he’d do that?” Lydia asked, and just in case anyone couldn’t tell the question was rhetorical, she winked and nodded at Jane and burst out laughing.

“Oh, thank you, Mr. Bennet!” Mrs. Bennet cried, and she swooped down on her husband and delivered one kiss after another to his forehead and cheeks. “Sweet, patient Mr. Bennet! Wily, crafty Mr. Bennet! Luring the baron here when you know how smitten he is with Jane! Oh, sly, shrewd Mr.—!”

“Enough!” cried flushed, flustered Mr. Bennet. “Lord Lumpley and I will be discussing unmentionables, not marriage!”

But Mrs. Bennet wasn’t listening.

“Hill! Hill? MRS. HILL!” she blared. “Where is that wretched woman when you really need—ah, there you are! We have so much to do to get ready! You must cut fresh flowers, polish the silver, launder the table linens, set out the girls’ best morning dresses … ooh, and run to the village for cakes! What? Which one first? Why, all of them, of course! The Baron of Lumpley is coming!”

Through it all, Lydia and Kitty whispered and tittered and snorted, ignoring Mary’s disapproving glowers (it falling to their sister to sit around looking dour and long-suffering now that Miss Chiselwood was gone).

Elizabeth and Jane, meanwhile, were exchanging significant looks of their own. Elizabeth’s was simultaneously concerned and fierce; Jane’s, discomfited and mildly reproachful. The two girls disagreed on few things, and one of them was about to pay them a call.

“You don’t seem as excited as your mother,” Mr. Bennet said dryly, eyeing first Elizabeth, then Jane.

“My excitement is merely of a different sort,” Elizabeth said.

“And I think it is premature for overexcitement of any sort,” said Jane.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

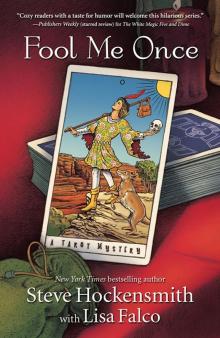

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

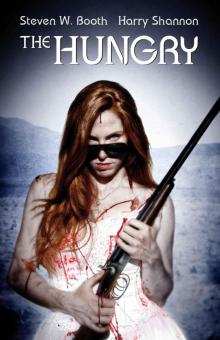

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

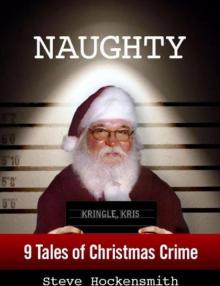

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

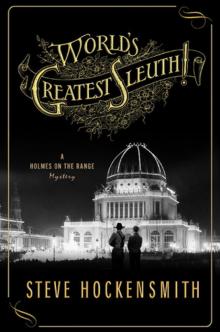

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!