- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

Dreadfully Ever After Page 4

Dreadfully Ever After Read online

Page 4

Elizabeth darted forward, took the letter, and started to tear it open while Mrs. Reynolds hovered anxiously nearby. All that the servants knew was that Darcy had been taken to Kent to be cared for by his aunt’s personal physician. With each day that passed without news of their injured master (or of the missing boy, Andrew Brayles), the household slipped deeper into gloom and despair.

Elizabeth pulled out the message—then remembered what it might contain.

“Thank you, Mrs. Reynolds,” she said, stuffing the letter back in its envelope. “I’ll be meditating if you need me for anything else.”

She left the housekeeper to wring her hands and furrow her brow on the front lawn.

Once Elizabeth was settled in the Shinto shrine that took up most of the east wing, she sat on the floor, crossed her legs, and took in forty soothing breaths while reciting her mantra exactly eighty times. Then she looked at the envelope in her hands.

It was addressed to “Elizabeth B.-D.,” and the pages inside contained no greeting line at all. “Elizabeth Darcy,” “Mrs. Fitzwilliam Darcy,” “Dear Elizabeth”—Lady Catherine obviously couldn’t bring herself to write any of it. Even that “B.” she had to slip in so as to somehow negate the “D.”

In lieu of empty pleasantries, her ladyship began her message with a warning.

Read quickly and commit all you see to memory, for you will have no record of what I tell you in but a few minutes’ time. You are about to learn secrets no one of your station has ever been privy to, and even a personage as high-born as I would lose everything—including my very life—if certain parties in London learned I had enlightened such as you. Should the undertaking I lay before you end in failure and your true intent be revealed, I will deny having told you anything of what follows, will accuse you of acquiring your knowledge of it through subterfuge and guile, and will, in fact, possess the loudest voice calling for your immediate execution.

If you now find your fortitude faltering, screw your courage to this: Darcy lives, but there can be no doubt that the plague is in him. Just this morning, I found him gnawing on his own toes in his sleep, and when I roused him he told me he’d been dreaming of eating boeuf bourguignon. His slide into the service of Satan has begun, and the serum will only slow that so long. If you still intend to honor your pledge to me, you must act immediately and in unswerving compliance with my instructions. If you do not so intend, stop reading here and begin planning your husband’s funeral.

First, the facts. The serum I once used on your friend, the unfortunate Mrs. Collins, was not, as I told you at the time, of my own creation, nor was it administered at its full strength. In truth, the elixir is made available, in miserly amounts, only to those of special interest to the Crown. Though its provenance has been kept secret even from them, there have been whispers in recent months that it has been improved to such a degree that, at long last, it might serve as an actual cure. These rumors inspired me to make my own private inquiries and, through much effort and expense, I have learned that the serum is the handiwork of one of the king’s personal physicians, Dr. Sir Angus MacFarquhar, and is most likely produced within the confines of the infamous cesspit of insanity and squalor he oversees—Bethlem Hospital. Though once open to the public, Bethlem today is a virtual fortress, and the loss of many a ninja has taught me that the place is impregnable. We must try a different tack if we are to acquire the cure before my nephew succumbs to the strange plague. We must go through Sir Angus himself.

This is the plan of attack: You shall take up residence in town posing as a nouveau-riche widow, you will throw yourself into Sir Angus’s path until a connection is established, and you will work your way into his confidence so completely that he will, intentionally or unintentionally, willingly or unwillingly, give us what we want. You will, in short, seduce and betray him. I have little doubt this task is within your power, for I’m told Sir Angus is a widower in desperate need of money, and what’s more you have already proved once before that you possess formidable skill when it comes to entrapping a man of rank high above your own.

If you intend to honor your side of our bargain and proceed along the path I propose, you need send no reply to say so. I have eyes everywhere. Your immediate departure for London will be assent enough. Enter the city at the Northern Guard Tower, name yourself at the gate as Mrs. Mathias Bromhead of Manchester, and you will be taken in hand from there. I, of course, will be engaged at Rosings, doing all in my power to save the life we both hold so dear.

You must do the same in London. No matter how shameful you might find your own actions to be, they are necessary, and that, as always, should trump either warrior’s pride or the squeamishness of weaklings.

You can have your precious honor or you can have your precious Darcy. One or the other must be set upon the pyre. Which it shall be I leave to you.

If you have reached these final lines without singeing your fingers, I would suggest depositing this letter in the nearest fireplace and standing back, for—

The pages in Elizabeth’s hands began to smoke of their own accord, and a split second after she dropped them, they burst into flame. By the time they’d finished their fluttering flight to the floor, there was little left but swirling ash and cinders.

Everything was rapidly crumbling to dust at Elizabeth’s feet, it seemed.

Everything.

CHAPTER 6

Oscar Bennet was a man who appreciated peace and quiet. Yet for years his library had been the only place he could find either. Out in the green fields of Hertfordshire were the shambling, ever-ravenous escapees from Hell that it was his sworn duty to return to Satan in as many pieces as possible. His home, meanwhile, had been invaded long ago by more alarming creatures still—a swarm of strong-willed females. One foe he fought fearlessly. In the face of the other, his preferred tactic had been, most frequently, retreat to his book-lined safe hold.

Things had changed in recent years. Oscar Bennet had peace, of sorts, if not always quiet. (His wife’s silences were like those of the battlefield: rare and brief and offering no relief, for they only gave one time to wonder what nerve-fraying onslaught might rain down next.) The dreadfuls still had to be dealt with, but the far fouler curse—that of unwed daughters and an estate entailed to a male relation—had been lifted. The Bennets’ eldest girls had been joined in marriage to wealthy men, and no longer would worries of dowries and entailments weigh on the family.

Scandal, too, was something Mr. and Mrs. Bennet no longer needed to fear, for their youngest daughter, Lydia, had also been successfully married off—the match being “successful” only in the sense that a ring was on her finger before a child was in her womb. Mr. Bennet considered this a great triumph, given Lydia’s character, which had been her own particular entailment from her mother. Lydia had always been a wild child, as much a slave to her impulses as any unmentionable, and it was a thing to savor that a husband, rather than her father, was accountable for her capriciousness. As Mrs. George Wickham, she was free to fill up the world with offspring as feckless and reckless as she, and this she had immediately set to doing. And if none of them looked a jot like Mr. George Wickham, what was that to Oscar Bennet?

Huzzah! Sweet freedom!

Yet Mr. Bennet had discovered something surprising about freedom from fear. It can be rather boring. Without challenges or strife or the struggle for something better and new, peace and quiet could seem very much like stagnation. It was, after all, peaceful and quiet in a grave. Or had been, once upon a time.

There was always an easy way to liven things up, though, especially in the spring when the undead emerged from the holes and caves and other hiding places in which they weathered the cold winter winds that stiffened them like snow-covered statues. One could go on patrol.

“I have yet to see a dreadful roosting in a tree,” Mr. Bennet said.

His second-youngest daughter, Catherine “Kitty” Bennet, was near the top of a particularly tall elm at the time, swinging from branch to

branch like a gown-wearing ape.

“I’m merely looking for the best vantage point from which to survey the area,” Kitty said.

“You are merely showing off,” her sister Mary replied. It was not really her place to criticize, Mr. Bennet thought, for she had spent the last hour idly spinning her katana with her right hand while holding up Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with her left. She knew the roads and footpaths of Hertfordshire so well she’d covered the last mile without once looking up from her book.

“Why would I bother showing off for you and Papa?” Kitty snipped back even as she did a double back-flip that sent her spinning to another branch.

“Because no young gentleman is around to show off for instead,” Mary said.

“Simply exercising one’s abilities is not showing off. At any rate, what respectable gentleman would take an interest in a girl who can do this?” Kitty grabbed a branch and swung around and around until the bark started chafing off under her calloused hands. “Or this?” She let go on an upswing, flinging herself to the top of the next tree. “Or this?” She executed a perfect swan dive, plummeting to within feet of the ground before grabbing the last available branch and slinging herself back to where she started.

Mary never stopped reading.

“Why should you care what a man makes of any of it?” she said.

“Because, unlike you, within me there resides a beating human heart, not an abacus for tallying the faults of others.”

“If you read more books like this”—Mary gave Wollstonecraft’s manifesto a little shake—“and fewer of those wretched novels you love so dearly, you would know the difference between the true concerns of the heart and the sentimental drivel peddled by romantic fantasists.”

“You just say that because you gave up on romance years ago. Why, I haven’t seen you give the handsomest man a second glance since Master Hawksworth went and—”

“Now you are being ridiculous!” Mary snapped.

Ridiculous or not, Kitty seemed to realize she’d gone too far. She ended the conversation with a groaned, “Oh, how I miss Lydia.”

As always, Mr. Bennet stayed out of the fray. It made him uncomfortable when Mary and Kitty discussed anything related to amour, for there was a reason such things remained, for them, hypotheticals and conjectures and not the stuff of real experience.

With three of the Bennets’ five daughters safely ensconced in the bonds of matrimony, his wife had abandoned the arranging of marriages and devoted herself instead to the preventing of them. She was determined that her unmarried daughters should remain her unmarried daughters—and, more important, her companions and nursemaids in her “declining years” (a phrase Mrs. Bennet was fond of repeating, even though, to judge by sheer verbiage, she was, if anything, on the incline). Mr. Bennet had much more faith in his wife’s abilities as a matchbreaker than he’d ever had in her as a matchmaker. Indeed, a mere five minutes in a drawing room with her had driven off more than one would-be suitor. As a result, Mary and Kitty had, for years now, no new suitors to drive off.

“Do you know what I’ve just realized?” Mr. Bennet said. “It has been forever since we checked the quarry at St. Albans. Do you remember the herd we found crammed into the old clay pit? All they could do was moan as we dropped rock after rock on them. Why, they were packed in together like a bunch of frozen kippers!”

Kitty gave her father’s jest (and his obvious attempt to change the subject) a half-hearted “La!”

Mary simply said, “To St. Albans, then?” But then she lowered her book and turned her head to the left.

Up in the treetops, Kitty stopped her acrobatics and turned to face the same direction.

Mr. Bennet didn’t hear the sound for another few seconds, but finally it penetrated his age-weakened ears: gasps and struggling and the creaking of strained rope.

Without a word, the Bennets followed the sound deeper into the forest. It wasn’t long before the smell came to them: Dead flesh lay ahead. The kind that gets up and walks around and tries to make more dead flesh.

Mr. Bennet raised the crossbow he’d been carrying. Mary tucked her book under her sword belt and put both hands on her katana. Kitty dropped out of the trees with her pistols drawn. A moment later, they reached the clearing. In its center was a single, ancient oak. From its thickest branch hung a woman with bulging eyes and a swollen purple face. She’d been dead about two days, Mr. Bennet judged. Time enough for her to decide she’d like to come down.

Zombies being zombies, of course, she wasn’t meeting with much success. Along with losing all scruples about eating other people, the undead awoke without the capacity for reason. All this particular dreadful could do was thrash and kick and spin in sad circles, dangling on its death rope.

When it saw the Bennets, it thrashed and kicked all the harder.

“See, Papa?” Kitty said. “They do sometimes roost in trees!”

“It’s Julia Goswick,” Mary observed.

If Kitty had been about to unleash another “La!” it never left her lips.

“Oh. So it is,” she said, sounding subdued (for her). Julia Goswick had been one of the Bennet girls’ prime romantic rivals, once. “I should have recognized that horrid morning dress straight off. I must say, she did quite a nice job with the rope. I would not have thought her capable of tying her own bonnet.”

Julia Goswick’s mortal remains swiped angrily at them every time its face spun in their direction.

“Do either of you have any idea why Miss Goswick would do such a thing to herself?” Mr. Bennet asked.

He got the answer he was expecting.

“She had been disappointed in love,” Mary said.

“People were starting to call her an old maid,” Kitty added. “She was four and twenty, you know.”

“I see.”

Kitty was twenty-one, Mary twenty-two.

“Foolish, emotional woman,” Mary spat with no shortage of her own emotion. “Mary Wollstonecraft says—”

“Mary.”

Kitty’s one word sufficed. Her sister fell silent.

“Well,” Mr. Bennet said, and he brought up his crossbow and shot a bolt through the rope holding Julia Goswick aloft. She landed on her feet, her ankles and knees splintering with audible pops. Kitty raised a pistol as the unmentionable staggered toward them on wobbly gelatin legs, its mouth gaping wide for a zombie roar that was strangled by the noose still tight around its neck.

Before Kitty could pull the trigger, Mary slipped in front of her and charged the zombie alone. She ducked under its first clumsy grab and then straightened and swung her katana.

The dreadful’s head slid slowly backward off its neck.

“I thought it might be best to be discreet,” Mary said as body followed crown into the underbrush, “without gunfire to explain to those who might overhear it.”

Mr. Bennet walked over to the corpse. “Good thinking.” (How very long it seemed since he’d said anything of that kind.) He removed a small flask from his pocket and liberally drizzled the contents over what was left of Julia Goswick. “We shall spare the family the shame of a suicide. Allow them to hope that she ran off to Edinburgh with some young rake.”

“Yes. A likely story,” Kitty said as the burn-acid did its work, the body bursting into hot, nearly smokeless flame. “And who could blame her?”

The Bennets waited silently until nothing remained but chunky ash. Then they cut down the rest of the rope and, by unspoken consensus, turned and headed for home. Kitty kept her feet on the ground all the way, Mary’s book remained closed, and no one spoke a word.

As was his way before heading into the house (and the company of his wife), Mr. Bennet sent his daughters ahead, retiring alone to his modest garden dojo for a quarter hour’s meditation. He sat on the floor, crossed his legs, closed his eyes, and silently repeated his mantra (“The soaring eagle sees all, hears nothing”) until he felt the serenity he needed to venture inside.

&n

bsp; He got only as far as his second “soaring eagle,” however, when a swirl of air, the slightest breeze stirred by furtive movement, blew across his face. Opening his eyes, Mr. Bennet found lying on the floor before him an envelope inscribed with his name. He looked around the dojo, leapt to his feet, and then dashed to the doorway, but the messenger was already gone.

Hears nothing, indeed. Someone practiced in stealth—a ninja, no doubt—had been hiding in the rafters or a weapons locker and managed to slip past him almost undetected.

He was getting old.

Mr. Bennet walked back to the envelope, picked it up, and opened it. The letter inside read thusly:

If you value the happiness of your daughter Elizabeth, you will come to London immediately. The life of her husband, my nephew, Fitzwilliam Darcy, hangs in the balance under circumstances that require the utmost secrecy. Should you reveal the reason for your journey, it would surely doom it to end in disaster—and would condemn you, I promise, to the death by a thousand cuts, each of them inflicted with no great haste by my own sword.

You may share the truth with but one person, for she is required in London also: that daughter of yours who has been favored both with my name and, I can only hope, enough discretion and skill not to dishonor it. Bring her with you to Massingberd’s, Colebrooke Row, One North, and your role in Mr. Darcy’s salvation will be made plain.

Fail to heed me, and you bring ruin upon not only him to whom you owe so much but also the daughter who has inveigled her way into his good graces and my ill.

The letter was unsigned, but there was no question from whom it came. Mr. Bennet read it quickly and then simply let it go, having recognized the smell and feel of Shinobi flash paper. He didn’t even glance down as the magnesium bound into the parchment reacted to the air and the oil on his fingers and ignited with the flickering white light of a shooting star. He would not dignify the spectacle with his attention. As far as he was concerned, the flash paper was a cheap, high-handed, melodramatic ploy—and, being designed to impress and intimidate him, it was entirely unnecessary. He was impressed and intimidated already.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

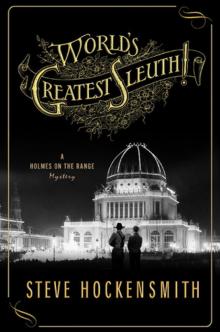

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!