- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove Page 4

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove Read online

Page 4

Chan shook his head and Old Red rolled his eyes, so I snatched up the fluffy white doughball and tore into it.

“Seems to me you wasn’t just ‘on edge,’ Doc,” my brother said. “You was prepared. I mean, you didn’t have that hideout gun back on the Express, did you? And either you’ve put on some weight the last month or you’re wearin’ some kinda paddin’ or armor under that suit of yours.”

Chan squirmed nervously in his chair, his fidgeting creating strange bulges and ripples in his clothes so obvious even I finally noticed them. The doctor was wearing something heavy and stiff under his shirt.

“I see your eye for detail is as sharp as ever,” he said. “Yes, I bought a gun. And a chain-mail vest. For protection. Hard times are coming for this country—and that means very hard times for the Chinese here. After the last Panic, two thousand members of the Anti-Coolie League marched into Chinatown and tried to burn it to the ground. The League doesn’t have that kind of strength again . . . yet. But every day, more of my countrymen are beaten senseless by hoodlums from North Beach and the Barbary Coast. I’m not going to let that happen to me.”

“Good for you, Doc,” I said through a mouthful of pork bun. “Half the time, all you gotta do to rid yourself of bullyin’ riff-raff is stand up to ’em.”

“And the other half of the time, the riff-raff slits your throat,” Gustav snipped at me. Then he turned back to Chan, and his voice softened. “Still, I gotta wonder . . . why would you think them ‘hoodlums’ would come after you?”

“Well, it’s not just me, of course. They’ll abuse any Chinaman they can get—”

Old Red shook his head, and Chan trailed off into silence.

“Before you popped off your shot at my brother, he shouted to you,” Gustav said. “Called you by name more than once. Yet you drew on him anyway. Which says to me you ain’t just afraid of bein’ roughed up randomlike. You think someone’s gunnin’ for you.”

Chan’s gaze drifted down to the table. Aside from that, he didn’t move—or speak.

“You got money problems, Doc?” my brother asked him. We were at a corner table, with no one else nearby, yet he dropped his voice down whisper-quiet all the same. “Owe somebody, maybe? Somebody mean?”

Chan stayed so utterly still it looked like he was in a staring contest with a plate of fried pork.

“Look. Me and Otto, we know why you was on the Pacific Express,” Gustav went on gently. “Found out the whole story ’fore the train took that dive over a mountainside. You was bringin’ back arty-facts from the Chinese exhibit at the World’s Fair in Chicago. Got ’em on loan—and guaranteed their safe return with your own cash, we was told. So when the Express wrecked . . . well, I was just wonderin’ if that wrecked you. Cuz if it did, maybe we could help out somehow.”

Of course, out here in the West, sticking your nose into another fellow’s financial affairs is roughly akin to sticking your finger in his eye. So Chan would’ve been within his rights to upend the nearest plate of delicacies over Old Red’s head.

“Thank you,” he said instead. He finally tore his gaze from the tabletop and looked at my brother, his expression somber. “You are very kind.”

Then his face changed, the lips curling into a wry smile, the flesh around his nose and eyes crinkling.

The eyes themselves, though—they remained just the same.

“But don’t worry about me,” Chan said. “I haven’t been ‘wrecked.’ Simply derailed temporarily. As the saying goes, I’m poorer but wiser. More poor than wise, perhaps, but I’ll even the scales again one day. And that’s all there is to it, really.”

He picked up his chopsticks and used them to nab himself another morsel of sauce-smeared pork.

“And what of you two? I didn’t see you mentioned in any of the newspaper articles about what happened on the Express. Are you still working for the railroad?”

My brother glanced over at me, raising one eyebrow ever so slightly.

That’s all there is to it? he was saying. I think not.

I replied with what to most men’s eyes would’ve looked like a simple twitch of the shoulders. Gustav, however, would recognize it for what it was: a resigned shrug.

You can lead a Chinaman to water. . . , I was saying.

“There’s a reason you didn’t read about us, Doc,” I said aloud. “The story they wrote up in the papers is grade-A S.P. bull crap. Here’s what really happened.”

Chan did his best to be a good audience as I filled him in on what he’d missed after getting tossed off the Pacific Express. He popped his eyes and gasped and shook his head in admiring wonderment in all the right places. Yet there was a feeling of play-acting about it—that overexpressive quality you notice too late when you’ve been boring the pants off somebody.

Not that I thought Chan wasn’t interested. My tale simply couldn’t compete with whatever was preying on the man’s mind.

“That’s amazing,” Chan said when I was done. “You should take your story to a newspaper or magazine. It would cause a sensation.”

“I couldn’t agree more, Doc,” I replied, about to reveal that those very wheels hadn’t just been set in motion, they were spinning full speed: The tale had already been put to paper and sent off to Smythe & Associates, publishers of Jesse James Library, Billy Steele—Boy Detective, and perhaps one day Big Red (and Old Red) Weekly. If Harper’s wouldn’t give my first book a good home, maybe Smythe & Associates would open its rather shabbier doors to my second.

But before I could tell Chan of my stabs at Watson-style scribing, there was a commotion at the front of the restaurant. After that, there was no use going on, for Chan was so gobsmacked I could’ve stuffed a string of firecrackers down his pants without winning his attention back.

Five Chinese men had trooped inside together. They didn’t move as most such groups would—two by three, maybe, or just jumbled up in a bunch. No, they were in a diamond: one in front, one in back, two to the sides, and one in the middle.

The fellows on the flanks and riding drag were all meaty, tall, black-clad, and (to judge by the stern looks on their broad faces) tough. The man taking point, on the other hand, had the wiry-scrappy-scrawny build of my brother, and his eyes scanned the room with the same all-seeing keenness. His gaze fastened for a moment on Old Red and me—and lingered even longer on Dr. Chan.

Yet Chan ignored the man. He was staring into the heart of the diamond, at a bright-eyed, good-looking Chinaman perhaps thirty years of age. His slender body was draped in silky, gaudy-patterned robes that may as well have been sewn together from ten-dollar bills, they were so showy. And the fellow had a regal bearing to match his finery, striding in with the chin-out, back-straight strut of a man of means who means for folks to know it.

Certainly, the restaurant’s owner knew. He grinned and stooped and bowed so low he could’ve kissed the metaphorical red carpet he was so cravenly rolling out. He led the party to the largest table available, an eight-seater in the middle of the room, but the short, sharp-eyed bodyguard (for bodyguard he plainly was) rejected it with a brusque shake of the head.

Two tables in the corner opposite ours were quickly commandeered, and the patrons already eating there scooped up their bowls and scurried off with nary a complaint.

“Who is that feller?” I asked under my breath as the bigshot settled into his chair and his guards took up positions around him. “Last I heard, Frisco hasn’t had an emperor since Norton the First passed away.”

“San Francisco may not have an emperor, but Chinatown does,” Chan whispered back. “That’s Fung Jing Toy.”

He paused, waiting for some indication that we felt the full weight of what he’d said. When he didn’t see any, he spoke again, his whisper so low this time I wasn’t sure if I actually heard the words or merely absorbed their meaning from the movement of his lips and the spooky expression on his face.

“Little Pete.”

“Holy shit,” I said. “I didn’t recognize him without h

is pitchfork and horns.”

Gustav’s response was a simple “Well, well.”

We’d been hearing about Little Pete almost nonstop for the last month. Nearly every day, I’d read out some new story in the local papers about him. Gambling halls, opium dens, whorehouses, “white slavery,” fixed sports of every stripe—Little Pete had a hand in so much sin and corruption he could almost compete with City Hall.

Yet finding ourselves in the presence of a bona fide Napoleon of crime wasn’t half as surprising as the look the man gave Chan.

He turned toward our friend the doctor . . . and he smiled.

Not as you might do to acknowledge a friendly acquaintance, though. More the way a fox might grin at a hen as he sneaks from the farm with another bloodied chicken a-twitching in his jaws. An “I’ll attend to you later” sort of smile. Almost a promise.

Apparently, the most dangerous man in San Francisco didn’t just know Dr. Gee Woo Chan. He had unfinished business with him.

5

A GOOD-BYE AND A HEL-LO

Or, Gustav Loses a Bet He Wants to Win and Wins One He Wants to Lose

Less than two minutes after Little Pete’s party came in, ours was going out. It wouldn’t be altogether fair to characterize Dr. Chan’s exit as a “skedaddle,” but neither was it a “mosey.” He threw down some wrinkled greenbacks without even asking for the tab, then hopped up and announced it was time to get back to work.

Little Pete didn’t seem to notice our departure, already being deep in conversation with the wiry Chinaman who’d been at the head of his procession. Yet, though the little henchman nodded and smiled and looked admiring as lackeys must, he never quite met his boss man’s gaze. Apparently, just giving the place the once-over wasn’t good enough for him—he was now giving it an eighth-over or ninth-over. Gustav and me he watched leave with a mixture of suspicion and smirky scorn, as if he was sizing us up as potential competition . . . and coming to the conclusion he had nothing to worry about.

Chan didn’t give Old Red a chance to ask more questions once we got outside, quickly launching into a fast-walking, fast-talking guided tour of the block. Up that way was a Buddhist temple. Down that way was the Presbyterian mission house. Yonder was a market with fish so fresh they were still gasping for breath. Over there one could buy “ghost money” to burn at an ancestor’s grave.

And here was Chan’s apothecary shop again. Good-bye.

An old Chinese man, stoop-shouldered and gray-bearded, was loitering out front of the store, and he drew closer as Chan gave me and my brother hurried farewell handshakes. The old-timer croaked something in Chinese as he shuffled up, his voice as rough as sandpaper on your privates, and Chan whirled on him and snapped a few harsh words in reply.

During our train trip together, I’d watched Chan withstand an onslaught of abuse from whites without once losing his air of kindness and quiet dignity. So what I was witnessing now—disdain on his face, a snarl in his voice—came as a shock. I’d read that the Chinese revere their elders, but there was no reverence here. Only contempt.

The two Chinamen exchanged a few words, the gravel-throated geezer wheedling and resentful, the doctor gruff and dismissive. It looked like Chan was about to brush right past the man into his shop, but something he heard stopped him, and the sneer on his face was swiftly swapped for surprise. After a little more back and forth with the old man, Chan turned to me and my brother again, his expression as pleasant as ever.

“Duty calls, it appears. Good-bye, Big Red. Old Red. I hope you’ll come visit me again soon.”

“Sure, Doc.” I tipped my hat—flashing him the still-tingling powder burn on my forehead. “Only next time, I’d appreciate it if your reception wasn’t quite so warm.”

Chan tried on a smile, but it didn’t fit him very well. “Pleasant” he could still manage. “Amused” was beyond him just then.

“Good luck, Doc,” my brother said.

Chan nodded stiffly, then swung back around to the old man and barked out what sounded like a command. They hurried away up the street side by side, but for as long as we stood there watching them, neither one turned to look at or speak to the other.

“There goes a peculiar pair,” Gustav said.

“The world’s full of ’em.” I jerked my head toward the southeast, where the Ferry House awaited us a dozen blocks away. “So . . . shall we retire to our Oakland chateau?”

Old Red gave me what I think of as Long-Suffering Stare Number Four. That’s the one where his eyebrows knit together, his thin lips purse, and the clenched set of his jaw adds a subtle hint of low-simmering anger.

“Don’t you wanna know what’s troublin’ Chan?”

“I am seething with barely restrained curiosity.” I shrugged. “And I also heard the man tell us it ain’t none of our damn business. Not in so many words, mind you, but it was there in between the lines. Hell, it was outside, under, and over the lines, too. He could’ve asked us for help. He didn’t. There it is. Time to go home.”

“And just forget about the doc?”

“Hey, you want a mystery to solve? I got one for you: Where is Diana Corvus?”

Long-Suffering Stare Number Four gave way to Exasperated Glower Number One.

“What? I won that bet.”

“You most certainly did not. Everything you said when you first spotted Chan was something we already knew. And here we are, an entire hour later, and all you’ve really deducified about the man is that there’s a lot more yet to deducify. Well, I am not impressed. Now if you think you should get another shot, fine. We’ll pick up where we were when Chan happened by. I’d say you had about fifteen seconds left to choose.” I stretched out my arms and turned to one side, then another. “Alright—get to it. Pick your man.”

Old Red just growled something unintelligible (and no doubt un-printable) and stomped away.

“That’s a forfeit, Brother!” I crowed as I started after him. “Ha! Sit tight, Diana—we’re comin’ to find ya!”

Whether Gustav had indeed conceded was hard to say, for he spoke not a word as we headed for the Ferry House. Even if he’d tried to put up an argument, there’s no guarantee I would have heard it. We were cutting across the city on a diagonal through the squalid tangle of groggeries, dancehalls, deadfalls, and whorehouses called the Barbary Coast, and the rough and rowdy neighborhood’s riotous din was well-nigh deafening. When one could make out actual words over the manic cacophony of the concert saloons and the general all-around roar of a thousand belligerent drunks all bellowing at once, they nearly always took the same form: shouted inducements (when approaching) and insults (if not stopping) from the prostitutes flashing their pallid flesh behind the bars of their bagnio “cribs.”

These siren songs held no sway over my brother and me, by the way. I wish I could say it was because my high moral fiber doesn’t allow for any truck with the flesh trade. Yet that, sadly, would be a lie. My morals are plenty fibrous on most matters, but when it comes to women, they’ve been known to go as soft as tapioca pudding.

No, the simple, rather unflattering truth of the matter is this: Gustav had ruined whoring for me years before.

“You know what I think about sometimes?” he said to me once in an El Paso saloon.

I’d been eyeing a dark-haired good-time gal all night and had just announced my intention to purchase her services—what would have been my first foray into the lion’s den of carnality as commerce.

“What’s that?” I muttered in reply, unable to tear my gaze from the beautiful and alluring (in hindsight, worn-out and drunk) woman who’d captured my heart . . . or parts due south, at least.

“What if our sisters was the last of the family left ‘stead of you and me?” Old Red said. “It could’ve happened easy enough. ‘Stead of you ridin’ out that flood that did everyone in, let’s say Use and Greta did. I’ve almost got myself killed a thousand times over droverin’. What if I wasn’t alive to come collect ’em afterward, like I done you? The farm

gone. All of us gone. What’s a couple young girls to do? Who looks after ’em? Where do they end up?”

By the time Gustav was done, I was no longer staring lustfully at that soiled dove—I was staring resentfully at him.

“You just cannot let me have any fun, can you?”

“Who’s stoppin’ your fun?” Old Red pulled a silver dollar from his pocket and plonked it onto the table. “There. On me. Have at it . . . Brother.”

“Fine. I will.”

I scooped up the coin and turned toward the object of my most un-brotherly affection—who suddenly bore an uncanny resemblance to the sisters I’d lost less than a year before.

“Oh, hell. You win,” I grumbled. “But I ain’t givin’ you your damn dollar back.”

After that, anytime I fell under the spell of some harlot’s charms, all my brother had to say was, “You know what I think about sometimes?”

To which I would grumpily reply, “Yes, I do. And thanks to you, now I think it, too.”

And that would be that.

Perhaps because I’ve been denied the usual outlet for a drover’s amorous impulses, I’ve fallen into the habit of falling in love with inappropriate women. A cattle baron’s wife, the mayor’s daughter, even an English noblewoman—I’m ever pining away after some lady so high born she can barely see a low-born like me for the clouds that swim through the skies between us.

So it was with Diana Corvus, though I didn’t know what line her father was in or how she’d come to be a Southern Pacific agent or whether one could find her (real?) name in the social registry. I did know, however, that the lady had style and grace—the kind that says, Too good for you, Otto Amlingmeyer without her even meaning it to. Her very unattainability represented a challenge I intended to accept . . . provided I ever saw her again.

During the ferry ride back to Oakland, Gustav and I passed the time in the company of our friend Sherlock Holmes, courtesy of Dr. Watson’s “A Scandal in Bohemia.” It was the best way we knew to keep Old Red from turning green. But the second we were back on solid ground, I was back on the subject of Diana Corvus.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

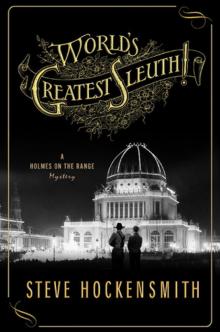

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!