- Home

- Steve Hockensmith

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 Page 7

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 Read online

Page 7

Master Hawksworth threw a quick, cold glare at Mr. Bennet, then shrugged off his coat and began unbuttoning his vest.

“Then I must demonstrate.”

His vest joined his coat on the floor. When he began untying his cravat, Elizabeth could actually feel the burn of the blush on her cheeks. For a moment, it looked as though he meant to take off his shirt, as well. He was merely loosening it, though, giving his broad chest room to do its work.

When he was ready, he threw himself facedown. Then he pushed up with his arms, and his body lifted, all his weight suspended on his palms and toes.

“One,” he said.

He lowered himself until his nose touched the floor, then pushed up again.

“Two.”

And so it went, all the way to fifty. It took him no more than half a minute.

He stood up again and looked at Kitty.

“Now you.”

Slowly, reluctantly, Kitty stretched out on the floor and attempted her first dand-baithak. Her arms shook under the strain of her weight, and by the time she could say “One” her face was as red as a beet.

“YOU!” Master Hawksworth barked, pointing at Mary this time. “Jump through the ceiling and catch me a swallow.”

It had always been one of Mary’s pleasures to learn from the mistakes of others, and this she tried to do again. She promptly got to her feet, stretched her arms out toward the ceiling, and hopped straight up with all her might.

Her feet made it all of four inches off the ground.

“I’m sorry, Master Hawksworth,” she said. “I missed.”

Master Hawksworth nodded. “But you did as I said without question.”

Mary smiled primly and began to sit down.

“And you failed!” Master Hawksworth snapped. “Fifty dand-baithaks.”

“But—”

“Sixty!”

“But—”

“Seventy!”

“But—”

“Eighty!”

Mary finally learned from her own mistake and got down on the floor.

“Master Hawksworth,” Lydia said, “before you ask, I can’t jump through the ceiling and catch you a swallow, either.”

“So I would assume.”

The Master stalked over to one of the weapons racks, pulled down a dagger, and held it out toward Lydia.

“You will kill that,” he jerked his head at a fly buzzing around where the daffodils used to be, “then skin it before it hits the ground.”

“You want me to skin a fly?”

“A novitiate never questions the master’s orders! Fifty dand-baithaks!”

Lydia stretched out beside her huffing, puffing sisters.

Elizabeth saw where all this was heading: Within a minute, Jane was doing dand-baithaks, too, for though she attacked the fly without question, she missed it with every slice of the knife.

Then it was Elizabeth’s turn.

“HAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA-IIIIIIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!” she cried, lunging at the fly.

It weaved under her first swipe. It danced around her second.

The third—to Elizabeth’s own amazement—sent it dropping to the floor. Dead.

“Not bad, Elizabeth Bennet,” the Master said. Yet his eyes said something more: When Elizabeth looked his way, she found him peering at her with what looked like naked—almost awestruck—fascination.

Master Hawksworth knelt down to inspect the fly lying before her.

“As at the lake, your zeal does you credit,” he said, his tone warming for a moment before freezing back into brittle ice. “A pity your skills do not. This fly has not been skinned—it has merely lost a wing.” He stood up with one hand held out. “Fifty dand-baithaks.”

Elizabeth gave him back the dagger and went to the floor at his feet.

“You look displeased, Oscar Bennet,” she heard Master Hawksworth say over her own panting and the roar of blood rushing in her ears. (The dand-baithaks were even more difficult than they looked.) “Do you wish to complain? If so, go ahead. I grant you dispensation this once.”

“Yes, I am displeased,” Mr. Bennet said. “It pains me to see my daughters so roughly treated.” Elizabeth caught the faint, familiar sound of one of her father’s sighs. “But no . . . I will not complain. We have been weak. I have been weak. I pray you will help us find our strength before it is too late.”

“I do, as well, Oscar Bennet. I do, as well. Now—there is a beetle in that corner. Behead it!”

Elizabeth heard the ka-chunk of a blade striking wood and holding fast. Then Master Hawksworth grunted.

“Not bad. You haven’t lost your old skills entirely, I see. But I told you to behead the beetle, not cut it in two.”

“Fifty dand-baithaks, Master?”

“For you, Oscar Bennet?” the young man said. “One hundred.”

CHAPTER 11

OVER THE NEXT TWO DAYS, the Bennet girls learned many new stances and moves and, along with their father, sparred with many new weapons.

There were, as a consequence, many, many mistakes and accidents—and many, many, many dand-baithaks.

Lydia titters when the Master squats, legs bent into a U, for “the Sumo Position”? Fifty dand-baithaks.

Mary accidentally knocks Kitty silly with her nunchucks? Fifty dand-baithaks.

Kitty un-accidentally knocks Mary silly with her nunchucks? Fifty dand-baithaks. For Mary again. For not dodging fast enough.

Mr. Bennet raises an eyebrow at Mary’s punishment? One hundred dand-baithaks and five laps around the grounds.

Jane quickly proved the most graceful disciple, and Mr. Bennet, of course, the most accomplished—so much so that Master Hawksworth frequently had him run his daughters through their drills while he stood back nodding gravely. Yet Elizabeth, with her piercing warrior’s cry and eagerness to try any maneuver or weapon, no matter the difficulty or danger, was without doubt the most ardent student in the dojo. Though why that should be even she couldn’t say.

Certainly, the Master never spoke of it. He rarely spoke of anything except how this is done right or this was done wrong or how many dand-baithaks were needed to make amends for one’s unworthiness. All the Bennets truly knew of him had to be sucked out as a leech draws blood—and there was, of course, but one leech for the job.

“A lovely English spring we’re having, is it not?” Mrs. Bennet said over dinner the day after Master Hawksworth’s arrival.

The Master didn’t even look up from his food, which he’d insisted on preparing himself. Not that it required much in the way of preparation: It was simply white rice and (to the obvious disgust of all, save Mr. Bennet) raw fish.

Up to then, Master Hawksworth had declared English cooking to be “bricks in a warrior’s stomach where fire out to be,” and at mealtimes he’d remained in the dojo to eat alone. Eventually, however, he’d been coaxed inside easily enough. All Elizabeth had to say was, “It would be an honor if you joined us this evening, Master,” and in he came.

“It’s probably been twenty years since we had so balmy an April,” Mrs. Bennet forged on.

Still Master Hawksworth said nothing.

“It was an unseasonably warm spring when The Troubles first began, as well,” Mary said. “It is my conjecture that the heat in some way accounts for the return of the dreadfOW!”

“What of the temperatures where you come from, Mr. Hawksworth?” Mrs. Bennet said, lifting the shoe heel from her daughter’s toes. “Do they range as unseasonably high?”

“Yes,” the Master said.

He reached out with the two smooth sticks he used in lieu of a proper fork or spoon, grabbed hold of a mound of rice, and stuffed it into his mouth. Mrs. Bennet waited patiently while he finished chewing so he could finish his thought, but he simply speared a floppy pink wad of fish and stuffed it in after the rice.

Mrs. Bennet grimaced and looked away, and when she again found her voice (which, alas, was never lost for long) she abandoned warmth as both a

topic of conversation and a model for her deportment.

“Well. I’m glad to see you’re enjoying your food . . . if you can call it that. You’ll find the streams of Hertfordshire overflowing with fat, juicy trout you may pluck out and tuck into at your leisure. If I may ask, where is it that you acquired a taste for such awfully fresh fare?”

“Japan.”

Hawksworth shoveled in more rice.

“Japan?” Mrs. Bennet said. “That’s the little island nation down around New South Wales, is it not? Full of Orientals?”

Hawksworth finally looked up from his plate—so he could scowl at Mrs. Bennet.

“Yes, yes,” Mr. Bennet mumbled, wincing. “That is the place.”

Elizabeth and Jane shared a wide-eyed glance. Master Hawksworth—a young man scarcely older than they—had actually traveled to Japan! If only he weren’t so stern and taciturn. There were so many questions to ask!

For Mrs. Bennet, however, there was only one.

“Such a long journey would surely cost a fortune. Your family could afford such a venture?”

“No,” Master Hawksworth said.

Mrs. Bennet frowned.

“But I have a patron for whom money is no object,” the Master added.

Mrs. Bennet smiled.

Master Hawksworth was looking at Mr. Bennet.

“I shan’t name names, yet I will say this: My benefactor has held true to the code others found it so easy to abandon once The Troubles were over. I was sent to Japan to learn and live by that code. Soon, your daughters will be living by it, as well. And perhaps dying by it . . . if they can earn such an honor.”

Mr. Bennet listened intently, solemnly, and when Hawksworth was finished, he replied with a single nod.

Mrs. Bennet, on the other hand, had stopped paying any attention whatsoever after the words “money is no object.”

“Tell me, Mr. Hawksworth,” she chirped, “do you like to dance?”

The Master froze with a glistening glob of raw flesh halfway to his face. “Pardon me?”

“In a little more than a week, there is to be a ball,” Mrs. Bennet said. “Some of our best local girls will be having their coming out—including our own Elizabeth. I’m sure you, as our guest, would be welcome.”

Master Hawksworth stared at Mrs. Bennet the same way she’d have stared at him had he stuck his eating sticks in his ears and mooed like a cow. After a moment, however, he overcame his dismay and reverted to his standard expression—which was, actually, an almost total lack of expression at all.

“I have no time for such frivolity, and neither do my students.”

“Your students?” Mrs. Bennet scoffed. And then, her voice edging toward panic as his meaning dawned on her: “Elizabeth? And Jane? But of course they must be at the ball.”

“When there is so much for them to learn and so little time to learn it?” Hawksworth shook his head. “I cannot allow it.”

“Who are you to allow or not allow anything here?”

“I am the Master.”

“Not of me, you’re not! And if I say Jane and Elizabeth are going to the ball, they’re . . . oh, you tell him, Mr. Bennet!”

“We will discuss this after dinner,” Mr. Bennet said softly. He seemed to be anticipating the conversation with all the enthusiasm of a condemned man looking ahead to his own hanging.

“Mr. Bennet!” his wife gasped. “You aren’t actually siding with this . . . this . . . whatever he is?”

“After dinner, woman.”

Which was answer enough for Mrs. Bennet.

“Ohhhhhhhhhh!” she cried, rolling her head and grabbing Mary with one hand, Kitty with the other. “My last hope, gone! Instead of throwing my eldest in the path of eligible bachelors, they’re to be thrown to the unmentionables! And so go the rest of us, girls—to a potter’s field or down a dreadful’s gullet, one or the other! And all because your father started taking orders from some ponytailed stripling who doesn’t even have the sense to cook his fish!”

Lydia and Kitty joined in with weeping of their own, and even Mary’s eyes took to watering behind her spectacles (though Elizabeth suspected this had more to do with the way her mother was crushing her hand).

When Elizabeth glanced at Hawksworth to gauge his reaction to this spectacle, she was surprised to find him intently gauging hers. He seemed both puzzled and approving at the same time, as if he were asking himself a question Elizabeth herself had considered often over the years: How did she come to be in the same family as her younger sisters and mother?

As Elizabeth watched, a placid blankness fell over the Master’s face, like a curtain being brought down on a play, and he looked away and rose from his seat.

“From now on,” he said calmly, picking up his plate, “I shall take all my meals in the dojo.”

Mr. Bennet watched him walk out with a look that was equal parts humiliation and jealousy. He then turned to his wife and undertook the fruitless task of calming her without outright giving in to her.

“I will speak to him in private, Mrs. Bennet. Our young friend doesn’t understand the full importance of the ball, that’s all.”

“Explain it to him, then! Tell him the estate is entailed away, and helping two of our daughters land husbands is the least he can do if he’s going to lead the other three to their doom!”

“Yes, well, there is more to the ball than the Master could guess, and I think he might change his mind once all the facts are laid out before him.”

“What do you—?” Elizabeth began.

Her mother talked right over her question, though—and kept on talking until the opportunity to ask it was gone.

“The Master! Oh, how it rankles to hear you speak of the pup thus. So rude, he is! So aloof! To think that our very survival should require you to grovel before a guest in our own home—and such an ungracious one, at that!”

And so on.

As it turned out, a guest in their home Hawksworth was not, for he not only finished his dinner in the dojo, from then on he did his sleeping there, as well. Mrs. Bennet regarded his retreat from the dining table and guest room as a victory over the man, and the next morning she had another: Her husband informed her that the Master had relented. Jane and Elizabeth could attend the ball after all. Unfortunately, Mrs. Bennet had but a few hours to savor her triumph.

Mr. Bennet and the girls were practicing new stances with their Master—and, consequently, working on the speed of their laps and the crispness of their dand-baithaks—when the scream rang out from the house. It was a shriek of pure horror, high and piercing, and it didn’t fade away but instead simply cut off, as if suddenly stifled.

Within seconds, Elizabeth and her father and sisters were charging inside, and they found Mrs. Bennet splayed out on the foyer floor. Her eyes were closed, and a kneeling Mrs. Hill was frantically fanning her with a piece of paper.

“My word!” the housekeeper cried. “I think she went and fainted for real, this time!”

“What happened?” Elizabeth asked.

“I don’t know! Mrs. Goswick’s man Bridges showed up with a letter, and she’d barely opened it before she was flat on her back!”

Mr. Bennet reached down and took the paper Mrs. Hill was using as a fan. She kept flapping her hand over Mrs. Bennet as he read the letter for all.

Mrs. Bennet,

It has come to our attention that your daughters, Miss Jane Bennet and Miss Elizabeth Bennet, have, of late, and at the behest of your husband, Mr. Bennet, become engaged in most remarkable, and one could even say shocking, activities (of a martial nature—I trust you will know what I mean). As the girls have, apparently, committed themselves to these brutal pursuits, we would not, of course, and with regrets for the invitation previously extended, expect to see them at so genteel an occasion as the ball we will be hosting, Thursday next, at Pulvis Lodge.

Yours etcetera, etcetera, Mrs. J. Goswick.

“By gad,” Mr. Bennet sighed when he reached the end. “The wretched woman

does love her commas.”

“Well, I think it was very kind of her to write as she did,” Mary said. “To be thinking of Jane and Elizabeth’s training when—”

“Oh, you stupid cow!” Lydia howled at her. “Don’t you see what this means? Jane and Elizabeth aren’t welcome at the spring ball. They’ve been told not to come! We’re ruined!”

“Now I’ll never get to go to a dance!” Kitty wailed. “Not even one!”

As Lydia and Kitty fell into each other’s arms weeping, Elizabeth simply waited for whatever her own reaction might be. Tears, anger, bitter laughter . . . what was it to be? And why didn’t it come more quickly?

Before she had her answer, Jane whirled around and ran up the stairs, her face in her hands. Elizabeth turned to go after her and found herself facing Master Hawksworth. He was about forty feet off, on the lawn, watching through the open front door. Yet the intensity of his gaze made her feel they were face to face, uncomfortably close.

Elizabeth stood there frozen, staring at the brawny, dark-haired man framed in the doorway, and the answer she’d been awaiting—the certainty she longed for—seemed to come nearer in that moment.

Then she heard the first of Jane’s sobs upstairs, and she had, if not an answer, at least a purpose, and one she couldn’t ignore.

She turned her back to the door and went after Jane. Yet even when she was on the stairs, well out of the Master’s line of sight, she could feel him watching her. It was as if he were searching for his own answer—one that lay buried somewhere, somehow, within her.

CHAPTER 12

EACH NIGHT, as had long been their custom, Jane and Elizabeth ended the day before the mirror in Jane’s room, talking and brushing each other’s hair. The only difference after nearly a week of training in the deadly arts was that now they were dressing each other’s wounds, as well.

That morning, their instruction under Master Hawksworth had reached a new stage. The girls weren’t merely practicing anymore. They were fighting—not just each other, but their father, too. Which meant they’d done a lot of losing, and losing a sparring match with a mace or a practice sword or even bare hands is bruising work.

Dawn of the Dreadfuls

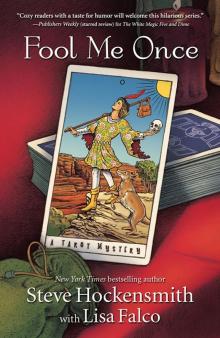

Dawn of the Dreadfuls Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery

Fool Me Once: A Tarot Mystery The Hungry

The Hungry Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime

Naughty: Nine Tales of Christmas Crime Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls papaz-1 The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery)

The White Magic Five & Dime (A Tarot Mystery) The Crack in the Lens

The Crack in the Lens Holmes on the Range

Holmes on the Range Dreadfully Ever After

Dreadfully Ever After S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove

S Hockensmith - H03 - The Black Dove On the Wrong Track

On the Wrong Track Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas

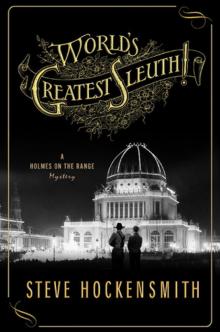

Naughty-Nine Tales of Christmas World's Greatest Sleuth!

World's Greatest Sleuth!